Making Paper in Exeter

by Barbara Rimkunas

This "Historically Speaking" column appeared in the Exeter News-Letter on Friday, July 19, 2013.

We don’t think of Exeter as a paper town, at least those of us who have lived in the vicinity of an actual paper-producing town don’t. Suffice to say that when residents of a paper mill town throw open the window and breathe in the morning air, their first thought isn’t “what a beautiful day,” it’s “I live in a paper town.” Paper towns, no matter how nice they are, have an identifiable aroma that stays with you. The sulfury smell – a bit like rotten eggs if the eggs were pickled first – is caused by the processing used to cook down wood into pulp. Locals say it smells like money.

Exeter wasn’t a paper town on the scale of Berlin or Gorham in upstate New Hampshire, but we did have a paper mill that operated for nearly 100 years. After the Revolution, Exeter’s lumber and shipbuilding industries had collapsed – primarily because the area was suffering from deforestation. New industries were needed to replace the old. In this void, printing and leather tanning began to grow in importance.

These two industries may not seem related unless you realize that books were bound in leather. Each could still exist without the other – Exeter’s books could have been bound in another place, like Portsmouth, and Exeter’s leather could have been sold to cobblers, tack shops or even carriage makers – but books had to be printed on paper. Paper was expensive and hard to come by in America. A local paper mill was a great idea.

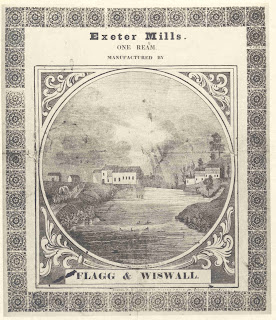

Richard Jordan erected his paper manufactory at King’s Falls (so named because the rights to the falls were granted, in 1652, to Thomas King) and ran it for ten years before selling it to Eliphalet and William Hale. They sold it to Stephen and Gideon Lamson in 1806, and they, in turn, sold it to Enoch Wiswall in 1813. Wiswall sold it to Thomas Wiswall, perhaps his brother, and he entered into a partnership with Isaac Flagg in 1815. For the next 60 years, the paper mill was known as “Flagg and Wiswall.”

Isaac Flagg had lived in Exeter since babyhood, he and his wife produced a large family and three of their sons eventually worked in the paper mill. The paper they produced was used throughout Exeter and sold to larger markets. The earliest examples of Exeter paper are poor in quality with disparities in thickness and ragged edges. This was commonly used for newspapers and not books. High quality paper was needed for the printers. Over time, the paper produced by Flagg & Wiswall improved to become the smooth and creamy paper that printers demanded.

Every few weeks, Flagg and Wiswall sent paper to Portsmouth – hiring Captain Joseph Fernald to ship it down the Squamscott. Fernald captained a small fleet of packets and gundalows that made regular trips up and down the river in the months that it wasn’t frozen. In his account book, Fernald lists the firm of “Wiswall and Flagg” and notes the shipments. Unlike almost every other citizen or merchant in Exeter, the paper mill stuck pretty much to business – shipments heading out included paper and pasteboard. Shipments back included ‘junk’ and rags. Also unlike most of his other customers, Flagg and Wiswall usually paid in cash. During the entire year of 1820, the firm only once paid Captain Fernald in fish.

Flagg and Wiswall needed the rags to produce their paper. Paper was made from the fibers of cotton, linen and wool textiles. Scraps of any kind were greatly appreciated – so much so, that the newspaper advertised for good quality rags. These were mixed with water and ground to a pulp and the resultant slurry was poured onto screens and dried into large sheets. These, in turn, were pressed or rolled to remove any remaining water, smoothed with sizing made of gelatin, dried and cut into uniform sheets. With the mill located away from the center of town and the process not using any sulfur agents, it never emitted the same aroma that identifies modern wood-based pulp and paper mills.

Flagg and Wiswall continued the business, passing down management to their sons, until 1871 when the mill was destroyed by a fire. The previous summer had been unusually hot and dry and the paper mill wasn’t the only casualty to fire that season. The Exeter Foundry and Machine Company and Phillips Exeter Academy both had major structures destroyed in the autumn of 1870. For Flagg and Wiswall, the fire was the end of the business. The remaining property was sold Exeter’s years as a paper town ended.

This "Historically Speaking" column appeared in the Exeter News-Letter on Friday, July 19, 2013.

We don’t think of Exeter as a paper town, at least those of us who have lived in the vicinity of an actual paper-producing town don’t. Suffice to say that when residents of a paper mill town throw open the window and breathe in the morning air, their first thought isn’t “what a beautiful day,” it’s “I live in a paper town.” Paper towns, no matter how nice they are, have an identifiable aroma that stays with you. The sulfury smell – a bit like rotten eggs if the eggs were pickled first – is caused by the processing used to cook down wood into pulp. Locals say it smells like money.

Exeter wasn’t a paper town on the scale of Berlin or Gorham in upstate New Hampshire, but we did have a paper mill that operated for nearly 100 years. After the Revolution, Exeter’s lumber and shipbuilding industries had collapsed – primarily because the area was suffering from deforestation. New industries were needed to replace the old. In this void, printing and leather tanning began to grow in importance.

These two industries may not seem related unless you realize that books were bound in leather. Each could still exist without the other – Exeter’s books could have been bound in another place, like Portsmouth, and Exeter’s leather could have been sold to cobblers, tack shops or even carriage makers – but books had to be printed on paper. Paper was expensive and hard to come by in America. A local paper mill was a great idea.

Richard Jordan erected his paper manufactory at King’s Falls (so named because the rights to the falls were granted, in 1652, to Thomas King) and ran it for ten years before selling it to Eliphalet and William Hale. They sold it to Stephen and Gideon Lamson in 1806, and they, in turn, sold it to Enoch Wiswall in 1813. Wiswall sold it to Thomas Wiswall, perhaps his brother, and he entered into a partnership with Isaac Flagg in 1815. For the next 60 years, the paper mill was known as “Flagg and Wiswall.”

Isaac Flagg had lived in Exeter since babyhood, he and his wife produced a large family and three of their sons eventually worked in the paper mill. The paper they produced was used throughout Exeter and sold to larger markets. The earliest examples of Exeter paper are poor in quality with disparities in thickness and ragged edges. This was commonly used for newspapers and not books. High quality paper was needed for the printers. Over time, the paper produced by Flagg & Wiswall improved to become the smooth and creamy paper that printers demanded.

Every few weeks, Flagg and Wiswall sent paper to Portsmouth – hiring Captain Joseph Fernald to ship it down the Squamscott. Fernald captained a small fleet of packets and gundalows that made regular trips up and down the river in the months that it wasn’t frozen. In his account book, Fernald lists the firm of “Wiswall and Flagg” and notes the shipments. Unlike almost every other citizen or merchant in Exeter, the paper mill stuck pretty much to business – shipments heading out included paper and pasteboard. Shipments back included ‘junk’ and rags. Also unlike most of his other customers, Flagg and Wiswall usually paid in cash. During the entire year of 1820, the firm only once paid Captain Fernald in fish.

Flagg and Wiswall needed the rags to produce their paper. Paper was made from the fibers of cotton, linen and wool textiles. Scraps of any kind were greatly appreciated – so much so, that the newspaper advertised for good quality rags. These were mixed with water and ground to a pulp and the resultant slurry was poured onto screens and dried into large sheets. These, in turn, were pressed or rolled to remove any remaining water, smoothed with sizing made of gelatin, dried and cut into uniform sheets. With the mill located away from the center of town and the process not using any sulfur agents, it never emitted the same aroma that identifies modern wood-based pulp and paper mills.

Flagg and Wiswall continued the business, passing down management to their sons, until 1871 when the mill was destroyed by a fire. The previous summer had been unusually hot and dry and the paper mill wasn’t the only casualty to fire that season. The Exeter Foundry and Machine Company and Phillips Exeter Academy both had major structures destroyed in the autumn of 1870. For Flagg and Wiswall, the fire was the end of the business. The remaining property was sold Exeter’s years as a paper town ended.

Comments