Exeter and the Declaration of Independence

by Barbara Rimkunas

This "Historically Speaking" column appeared in the Exeter News-Letter on Friday, July 5, 2013.

It’s pretty quiet in Exeter on the Fourth of July. Most likely, it was pretty quiet back on July 4th, 1776, when things at the Continental Congress in Philadelphia became very, very exciting. On that day, representatives of the American Colonies of Great Britain became the United States of America. But the news didn’t reach New Hampshire for another two weeks.

After the vote for independence was taken and the declaration was approved, a draft copy was sent to the print shop of John Dunlap for a rush printing job. Copies were needed to get the word out – the question of independency had been debated for months. John Hancock, then serving as the President of Congress, ordered that copies of the document be sent to the various colonies – now ‘states’ of the new union.

On July 16th, the Committee of Safety in Exeter sent a reply to John Hancock: “Sir, This moment the Committee were Honoured with the receipt of your letter of the 6th inclosing a Declaration separating the United States of America from any connection with Great Britain, and for their being Independent States. It is with pleasure we assure you, that notwithstanding a very few months since many Persons in this Colony were greatly averse to any thing that look’d like Independence of Great Britain, the late measures planned & Executing against us, have so altered their opinions that such a Declaration was what they most ardently wished for; and I verily believe it will be received with great satisfaction throughout the Colony, a very few Individuals excepted.”

In a post script, it was noted, “The General Court and Committee of Safety sit at Exeter, where you will please to direct in future. This Express went 30 miles out of his way by being directed to Portsmouth.”

The Declaration of Independence was quickly copied and Robert Luist Fowle, a local printer, published it in a special edition of the New England Gazette dated that same day - July 16th. It was publicly read aloud on the steps of the Exeter Town House by a young John Taylor Gilman. Gilman was the son of New Hampshire State Treasurer, Nicholas Gilman Sr. Among the people who gathered to hear it read was Matthew Thornton, who would later sign the official copy in Philadelphia joining the other members of the New Hampshire delegation, Josiah Bartlett and William Whipple.

Where the New Hampshire copy went after its public reading is something of a mystery. It was, after all, considered a piece of ephemera – a piece of paper meant to be read and then disposed of. Then, in 1985, a Dunlap Broadside, as this printing is called, was found in the attic of the Ladd-Gilman house (known as Cincinnati Memorial Hall) in downtown Exeter by some electricians including Dick Brewster. The building was owned by the New Hampshire Society of the Cincinnati – an organization of the male descendants of George Washington’s officer corps. Realizing that they had found a valuable document, the New Hampshire Society members decided to sell it and use the money to fund scholarships and upkeep on the building.

This all came to a crashing halt when the State of New Hampshire, believing it to be the official broadside sent by Hancock, declared it to be the property of the state. The legal wrangling lasted five years before it was decided to share the document. The state reserves the right to display the document up to 100 days per year. And from this agreement, the American Independence Museum was founded in 1991.

For two centuries Exeter, like the rest of the nation, celebrated independence – often quite loudly and with casualties – on the 4th of July. Gradually, however, after the American Independence Museum began hosting “Revolutionary War Days”( in coordination with the town’s Old Home Days, which had settled into mid-July), a more focused approach to the festival began to develop. Called the Revolutionary War Festival until 2006, the American Independence Festival has come to reflect our expression of how the events of 1776 actually played out. The arrival and reading of the Declaration of Independence continues to be the highlight of the event, although many would argue that anything that brings soft-serve ice cream and fried dough to town is welcome. The often raucous concert on Swasey Parkway in the evening brings out large crowds to celebrate and watch fireworks. So what if Exeter is a ghost town on July 4th – at least we’re authentic.

John Adams wrote to Abigail that “I am apt to believe that it will be celebrated, by succeeding Generations, as the great anniversary Festival. It ought to be commemorated, as the Day of Deliverance by solemn Acts of Devotion to God Almighty. It ought to be solemnized with Pomp and Parade, with Shews, Games, Sports, Guns, Bells, Bonfires and Illuminations from one End of this Continent to the other from this Time forward forever more." Of course, he was talking about July 2nd – the day the Second Continental Congress voted for independence. They would vote to adopt the Declaration of Independence on July 4th. In Exeter, we’ll take July 16th as our “great anniversary Festival.”

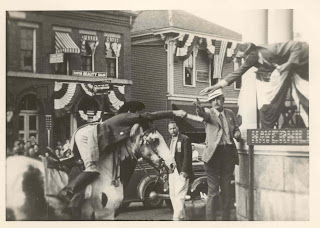

Photo caption: Exeter reenacts the arrival of the Declaration of Independence during the Tercentenary Celebrations in 1938.

This "Historically Speaking" column appeared in the Exeter News-Letter on Friday, July 5, 2013.

It’s pretty quiet in Exeter on the Fourth of July. Most likely, it was pretty quiet back on July 4th, 1776, when things at the Continental Congress in Philadelphia became very, very exciting. On that day, representatives of the American Colonies of Great Britain became the United States of America. But the news didn’t reach New Hampshire for another two weeks.

After the vote for independence was taken and the declaration was approved, a draft copy was sent to the print shop of John Dunlap for a rush printing job. Copies were needed to get the word out – the question of independency had been debated for months. John Hancock, then serving as the President of Congress, ordered that copies of the document be sent to the various colonies – now ‘states’ of the new union.

On July 16th, the Committee of Safety in Exeter sent a reply to John Hancock: “Sir, This moment the Committee were Honoured with the receipt of your letter of the 6th inclosing a Declaration separating the United States of America from any connection with Great Britain, and for their being Independent States. It is with pleasure we assure you, that notwithstanding a very few months since many Persons in this Colony were greatly averse to any thing that look’d like Independence of Great Britain, the late measures planned & Executing against us, have so altered their opinions that such a Declaration was what they most ardently wished for; and I verily believe it will be received with great satisfaction throughout the Colony, a very few Individuals excepted.”

In a post script, it was noted, “The General Court and Committee of Safety sit at Exeter, where you will please to direct in future. This Express went 30 miles out of his way by being directed to Portsmouth.”

The Declaration of Independence was quickly copied and Robert Luist Fowle, a local printer, published it in a special edition of the New England Gazette dated that same day - July 16th. It was publicly read aloud on the steps of the Exeter Town House by a young John Taylor Gilman. Gilman was the son of New Hampshire State Treasurer, Nicholas Gilman Sr. Among the people who gathered to hear it read was Matthew Thornton, who would later sign the official copy in Philadelphia joining the other members of the New Hampshire delegation, Josiah Bartlett and William Whipple.

Where the New Hampshire copy went after its public reading is something of a mystery. It was, after all, considered a piece of ephemera – a piece of paper meant to be read and then disposed of. Then, in 1985, a Dunlap Broadside, as this printing is called, was found in the attic of the Ladd-Gilman house (known as Cincinnati Memorial Hall) in downtown Exeter by some electricians including Dick Brewster. The building was owned by the New Hampshire Society of the Cincinnati – an organization of the male descendants of George Washington’s officer corps. Realizing that they had found a valuable document, the New Hampshire Society members decided to sell it and use the money to fund scholarships and upkeep on the building.

This all came to a crashing halt when the State of New Hampshire, believing it to be the official broadside sent by Hancock, declared it to be the property of the state. The legal wrangling lasted five years before it was decided to share the document. The state reserves the right to display the document up to 100 days per year. And from this agreement, the American Independence Museum was founded in 1991.

For two centuries Exeter, like the rest of the nation, celebrated independence – often quite loudly and with casualties – on the 4th of July. Gradually, however, after the American Independence Museum began hosting “Revolutionary War Days”( in coordination with the town’s Old Home Days, which had settled into mid-July), a more focused approach to the festival began to develop. Called the Revolutionary War Festival until 2006, the American Independence Festival has come to reflect our expression of how the events of 1776 actually played out. The arrival and reading of the Declaration of Independence continues to be the highlight of the event, although many would argue that anything that brings soft-serve ice cream and fried dough to town is welcome. The often raucous concert on Swasey Parkway in the evening brings out large crowds to celebrate and watch fireworks. So what if Exeter is a ghost town on July 4th – at least we’re authentic.

John Adams wrote to Abigail that “I am apt to believe that it will be celebrated, by succeeding Generations, as the great anniversary Festival. It ought to be commemorated, as the Day of Deliverance by solemn Acts of Devotion to God Almighty. It ought to be solemnized with Pomp and Parade, with Shews, Games, Sports, Guns, Bells, Bonfires and Illuminations from one End of this Continent to the other from this Time forward forever more." Of course, he was talking about July 2nd – the day the Second Continental Congress voted for independence. They would vote to adopt the Declaration of Independence on July 4th. In Exeter, we’ll take July 16th as our “great anniversary Festival.”

Photo caption: Exeter reenacts the arrival of the Declaration of Independence during the Tercentenary Celebrations in 1938.

Comments