The Reverend Samuel Dudley

by Barbara Rimkunas

This "Historically Speaking" column appeared in the Exeter News-Letter on Friday, May 24, 2013.

In Exeter, as in most of New England in the 1600s, the most important man in town was the minister. The Reverend John Wheelwright had organized Exeter in 1638, but had been forced to leave when the townsmen voted to align themselves with the Massachusetts Bay Colony just five years later. Some of Wheelwright’s followers left with him, but many remained and quietly absorbed newcomers who arrived after Wheelwright’s departure. Although the town was able to govern itself with elders and selectmen, not having a spiritual leader weighed heavily on the inhabitants.

Wheelwright had hoped that his friend Thomas Rashleigh would accept the job, but Rashleigh refused for his own reasons. A substitute, the Reverend Hatevil Nutter of Dover, was asked to fill-in while the town searched for a new permanent minister. It was a time when money was in short supply, and so the Rev. Nutter was paid not with cash but with service. He owned a tract of land on the Lamprey River and it needed fencing. Every year, the townsmen of Exeter were required to donate time and materials to enclose the property. After five years, the job was done, the Reverend Nutter signed the town book acknowledging the work was done and his services were no longer needed. Fortunately, by that time, June of 1650, the search committee had located a new preacher when the Reverend Samuel Dudley accepted the call to come to Exeter.

It had been difficult finding someone to serve the town. There were few trained ministers available and Exeter had little to offer. It was still a fledgling community; the only resources in town were trees and fish. Several times, the committee had made offers to likely candidates, only to see the deal fall through. To attract Dudley, they had to make his commitment worth the privations he would have to endure. In exchange for his services, Mr. Dudley was to receive Wheelwright’s house, garden and cow-house – all of which needed some renovations before he could move in. He would also receive £40 a year as pay. The particulars are written into a contract that was transcribed into the town records, “it is further agreed upon that the old cow-house, which was Mr. Wheelwright’s, shall by the town be fixed up fit for the settling of cattle in, and that the aforesaid pay of £40 a year is to be made in good pay every half year, in corn and English commodities at a price current, as they go generally in the country at the time or times of payment.”

There was very little actual money circulating in the colonies during this time and commerce was done with a barter system similar to the Rev. Dudley’s contract. To pay the minister his due, townsmen were taxed based on the number of pipe staves, hogshead staves or bolts that they produced. These were finished pieces of saleable lumber that the people used as currency. The tax rate, as listed in the town records, was, “for every thousand of pipe staves he makes, two shillings, which shall be for the maintenance of the ministry; and for every thousand of hogshead staves, one shilling sixpence; and for every thousand of bolts sold before they be made into staves, four shillings.” All the lumber had to be delivered to the wharf twice annually and would be shipped down the river to Portsmouth or Boston to be exchanged for “English commodities.” The type of goods that were collected was not listed, but one can imagine Mr. Dudley received bolts of cloth, tea and rum for his efforts. Some of these he would no doubt trade around town in exchange for other goods. It was a complicated system – how much was one yard of cloth worth? Perhaps two or three chickens?

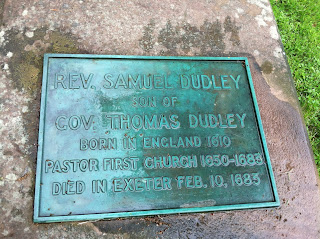

Dudley came to the town well-recommended from Massachusetts. He was the son of Governor Thomas Dudley and, although not university trained, had studied hard under his father’s tutelage and was considered well-qualified to preach. His first wife, Mary, had been the daughter of Governor John Winthrop. After Mary’s death in Salisbury, Dudley had married Mary Byley of Salisbury. She was his wife when he arrived in Exeter in 1650. After her death, he married a third time, to Elizabeth Smith of Exeter. The succession of wives bore him eighteen children, a sure sign of God’s grace to the people of that era.

Quite often during his tenure, the town was incapable of paying him the promised £40. To keep him in town, he was granted land and water rights. At the time of his death, his personal inventory showed him to be a man of means and great commercial instincts.

Dudley remained in Exeter and served as minister for thirty-three years. Charles Bell, author of the “History of Exeter, New Hampshire,” comments that, “there was no visible sign of failure of the powers, physical or mental, of Mr. Dudley, as he drew on to old age. When he was sixty-nine, he was appointed upon a committee for the equal distribution of the of the town lands, a duty which no feeble man would have been selected to perform.” He died in Exeter in 1683 and was buried, according to tradition, in the small cemetery on Green Street.

This "Historically Speaking" column appeared in the Exeter News-Letter on Friday, May 24, 2013.

In Exeter, as in most of New England in the 1600s, the most important man in town was the minister. The Reverend John Wheelwright had organized Exeter in 1638, but had been forced to leave when the townsmen voted to align themselves with the Massachusetts Bay Colony just five years later. Some of Wheelwright’s followers left with him, but many remained and quietly absorbed newcomers who arrived after Wheelwright’s departure. Although the town was able to govern itself with elders and selectmen, not having a spiritual leader weighed heavily on the inhabitants.

Wheelwright had hoped that his friend Thomas Rashleigh would accept the job, but Rashleigh refused for his own reasons. A substitute, the Reverend Hatevil Nutter of Dover, was asked to fill-in while the town searched for a new permanent minister. It was a time when money was in short supply, and so the Rev. Nutter was paid not with cash but with service. He owned a tract of land on the Lamprey River and it needed fencing. Every year, the townsmen of Exeter were required to donate time and materials to enclose the property. After five years, the job was done, the Reverend Nutter signed the town book acknowledging the work was done and his services were no longer needed. Fortunately, by that time, June of 1650, the search committee had located a new preacher when the Reverend Samuel Dudley accepted the call to come to Exeter.

It had been difficult finding someone to serve the town. There were few trained ministers available and Exeter had little to offer. It was still a fledgling community; the only resources in town were trees and fish. Several times, the committee had made offers to likely candidates, only to see the deal fall through. To attract Dudley, they had to make his commitment worth the privations he would have to endure. In exchange for his services, Mr. Dudley was to receive Wheelwright’s house, garden and cow-house – all of which needed some renovations before he could move in. He would also receive £40 a year as pay. The particulars are written into a contract that was transcribed into the town records, “it is further agreed upon that the old cow-house, which was Mr. Wheelwright’s, shall by the town be fixed up fit for the settling of cattle in, and that the aforesaid pay of £40 a year is to be made in good pay every half year, in corn and English commodities at a price current, as they go generally in the country at the time or times of payment.”

There was very little actual money circulating in the colonies during this time and commerce was done with a barter system similar to the Rev. Dudley’s contract. To pay the minister his due, townsmen were taxed based on the number of pipe staves, hogshead staves or bolts that they produced. These were finished pieces of saleable lumber that the people used as currency. The tax rate, as listed in the town records, was, “for every thousand of pipe staves he makes, two shillings, which shall be for the maintenance of the ministry; and for every thousand of hogshead staves, one shilling sixpence; and for every thousand of bolts sold before they be made into staves, four shillings.” All the lumber had to be delivered to the wharf twice annually and would be shipped down the river to Portsmouth or Boston to be exchanged for “English commodities.” The type of goods that were collected was not listed, but one can imagine Mr. Dudley received bolts of cloth, tea and rum for his efforts. Some of these he would no doubt trade around town in exchange for other goods. It was a complicated system – how much was one yard of cloth worth? Perhaps two or three chickens?

Dudley came to the town well-recommended from Massachusetts. He was the son of Governor Thomas Dudley and, although not university trained, had studied hard under his father’s tutelage and was considered well-qualified to preach. His first wife, Mary, had been the daughter of Governor John Winthrop. After Mary’s death in Salisbury, Dudley had married Mary Byley of Salisbury. She was his wife when he arrived in Exeter in 1650. After her death, he married a third time, to Elizabeth Smith of Exeter. The succession of wives bore him eighteen children, a sure sign of God’s grace to the people of that era.

Quite often during his tenure, the town was incapable of paying him the promised £40. To keep him in town, he was granted land and water rights. At the time of his death, his personal inventory showed him to be a man of means and great commercial instincts.

Dudley remained in Exeter and served as minister for thirty-three years. Charles Bell, author of the “History of Exeter, New Hampshire,” comments that, “there was no visible sign of failure of the powers, physical or mental, of Mr. Dudley, as he drew on to old age. When he was sixty-nine, he was appointed upon a committee for the equal distribution of the of the town lands, a duty which no feeble man would have been selected to perform.” He died in Exeter in 1683 and was buried, according to tradition, in the small cemetery on Green Street.

Comments

eewhitneyjr@gmail.com