Home Delivery

by Barbara Rimkunas

This "Historically Speaking" column was published in the Exeter News-Letter on Friday, May 8, 2020.

Remember back when you could run to the supermarket because you needed two items? Wait, that was just a few months ago. Before we lived in pandemic lockdown, having our groceries delivered to the house seemed like something that only fancy – or perhaps lazy – people did. The convenience of being able to pop into the store with no preplanning and no special safety gear says something about our definition of ‘convenience.’ It is convenience based on our ease of mobility. We travel to the food, rather than the food traveling to us. It wasn’t always this way.

There is a myth that yeoman farmers produced everything they needed. But in reality, intricate systems of trade provided communities with resources, particularly where foodstuffs were concerned. The difference between food subsistence and food abundance was often transportation. Granted, in earlier times, say the nineteenth century, we shopped and cooked differently. If you buy flour by the barrel because you bake bread every week, it’s going to be tricky carrying it home. Not everyone owned a horse and wagon. There were household necessities that simply had to be hauled home. Digging through the old town directories and newspapers, there were, in 1887, numerous ‘provisions’ that people purchased on a regular basis – flour, sugar, coal, ice, meats, fish, molasses, salt. There were 14 businesses that listed themselves as ‘grocers.’ Eleven of these were located on Water Street. The other three were on Portsmouth Avenue, High Street at the corner of Portsmouth Avenue and Front Street. Not exactly a case of ‘location, location, location’ driving these businesses. But it didn’t matter where the grocers were in relation to the customers, it mattered where they were in relation to how the goods arrived. In 1887, most goods were still arriving by water or rail. All the shops were clustered around the center of town. The customers did not browse through aisles of goods picking things out. Rather, they would send notice to the storekeeper who would then deliver goods directly to the home. Competition was based on this service. The grocer who could accurately provide the best product – quickly delivered – lured the most customers. It was simply bad service to expect the customer to travel to the shop. It might take 30 minutes to walk to the center of town, often in poor weather, often with small children in tow and usually without any practical means to haul everything home. No, it had to be delivered.

In 1887, George F. Lord advertised “Choice Family Groceries” that included tea, coffee and spices, canned fruits and vegetables, confectionery, tobacco, cigars – also, “ALL THE POPULAR BRANDS OF FLOUR.” F.J. Sanborn, who had his shop just outside of the center of town – on “Portsmouth Ave opposite the Reservoir” – offered “Meats and Provisions, choice beef, mutton, lamb, veal, pork, bacon, tongues, poultry and game in season.” And he added, to reassure his customers, “goods promptly delivered in any part of the village.” Along with foodstuffs, townspeople could order ice, for the ice box, coal for fuel, and laundry service. Laundry was a horrible chore that involved hauling and heating gallons of water, lifting wet heavy clothes, line drying and hours of tedious ironing. Although done less frequently than we do laundry today, this was not out of frugality as much as exhaustion. Efficient homes required all occupants to rinse out their small things each evening, but eventually everything would need a good washing. In 1887, there were two laundries in town offering services. To sweeten the deal, the Exeter Steam Laundry began offering free pick up and delivery in 1897. Other laundries quickly opened with the same services. “Our collecting days Mondays and Thursdays,” advertised the Steam Laundry, “call cards have been distributed, others can have them on application.”

Housewives took to the delivery system with enthusiasm. Lists were sent to merchants via small children or by postal card. Mail was delivered several times each day – another service that expanded in previous years only to contract later. Ice was ordered by placing a sign in the window. The ice wagon would arrive at its own pace, servicing the customers along his route. Milk carts, like ice wagons, delivered to regular customers. People who had milk delivered often contracted with individual farmers. There were no dairies advertising until the 1920s. The sanitary milk bottle was not invented until the late 1880s and wasn’t in common use until the 1890s. Before that, a farmer would deliver milk from open cans using a dipper to dispense the required amount into a housewife’s pitcher. After the 1920s when milk was considered safe and sanitary thanks to pasteurization and modern bottling, milk delivery (as well as consumption) went way up.

There were fewer bakeries in the 1880s. Most people did the bulk of their everyday baking at home. The convenience of bread delivery arrived after the turn of the century. Like dairies, bakeries offered delivery direct from the business with no showroom needed.

The heydays of home delivery were the early decades of the twentieth century. When telephones were introduced, it was the local merchants who became early adopters. By the time, the 1911 directory was published, no grocer was foolish enough to advertise without mentioning telephone ordering. The convenience to a housewife on Washington Street to simply dial the grocer, order meats, canned vegetables and maybe something she’d seen advertised (“Moxie – Nerve Food – Refreshes, strengthens, is healthful and nourishes worn-out nerves of mind and body, this great temperance beverage – Your grocer will take it to your house!” Order it by name!), must have seemed very modern. Milk was delivered daily, bread several times each week. The fish wagon arrived once a week. Higgins Ice Cream delivered “at short notice” lest the product melt.

And if you chipped a glass, burned the frying pan or needed a new wash tub, there was always the Sears and Roebuck or Montgomery Ward catalog. They were the Amazon of their day – undercutting local dealers and allowing the customer to browse through the merchandise from the comfort of home, and everything was shipped right to the house.

If all this sounds like the perfect system for surviving a quarantine, keep in mind that, despite all this convenience, the state of medicine at the time was scary. Few vaccinations, no antibiotics, rampant tuberculosis, measles, mumps, influenza, chicken pox. A blister could kill you. All the more reason to stay at home. Stay at home. We’ll get through this.

Barbara Rimkunas is curator of the Exeter Historical Society. Support the Exeter Historical Society by becoming a member! Join online at: www.exeterhistory.org

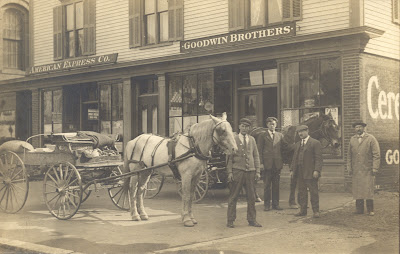

Image: Goodwin Brothers Grocers on Water Street in Exeter pose with their delivery wagon, c. 1900.

This "Historically Speaking" column was published in the Exeter News-Letter on Friday, May 8, 2020.

Remember back when you could run to the supermarket because you needed two items? Wait, that was just a few months ago. Before we lived in pandemic lockdown, having our groceries delivered to the house seemed like something that only fancy – or perhaps lazy – people did. The convenience of being able to pop into the store with no preplanning and no special safety gear says something about our definition of ‘convenience.’ It is convenience based on our ease of mobility. We travel to the food, rather than the food traveling to us. It wasn’t always this way.

There is a myth that yeoman farmers produced everything they needed. But in reality, intricate systems of trade provided communities with resources, particularly where foodstuffs were concerned. The difference between food subsistence and food abundance was often transportation. Granted, in earlier times, say the nineteenth century, we shopped and cooked differently. If you buy flour by the barrel because you bake bread every week, it’s going to be tricky carrying it home. Not everyone owned a horse and wagon. There were household necessities that simply had to be hauled home. Digging through the old town directories and newspapers, there were, in 1887, numerous ‘provisions’ that people purchased on a regular basis – flour, sugar, coal, ice, meats, fish, molasses, salt. There were 14 businesses that listed themselves as ‘grocers.’ Eleven of these were located on Water Street. The other three were on Portsmouth Avenue, High Street at the corner of Portsmouth Avenue and Front Street. Not exactly a case of ‘location, location, location’ driving these businesses. But it didn’t matter where the grocers were in relation to the customers, it mattered where they were in relation to how the goods arrived. In 1887, most goods were still arriving by water or rail. All the shops were clustered around the center of town. The customers did not browse through aisles of goods picking things out. Rather, they would send notice to the storekeeper who would then deliver goods directly to the home. Competition was based on this service. The grocer who could accurately provide the best product – quickly delivered – lured the most customers. It was simply bad service to expect the customer to travel to the shop. It might take 30 minutes to walk to the center of town, often in poor weather, often with small children in tow and usually without any practical means to haul everything home. No, it had to be delivered.

In 1887, George F. Lord advertised “Choice Family Groceries” that included tea, coffee and spices, canned fruits and vegetables, confectionery, tobacco, cigars – also, “ALL THE POPULAR BRANDS OF FLOUR.” F.J. Sanborn, who had his shop just outside of the center of town – on “Portsmouth Ave opposite the Reservoir” – offered “Meats and Provisions, choice beef, mutton, lamb, veal, pork, bacon, tongues, poultry and game in season.” And he added, to reassure his customers, “goods promptly delivered in any part of the village.” Along with foodstuffs, townspeople could order ice, for the ice box, coal for fuel, and laundry service. Laundry was a horrible chore that involved hauling and heating gallons of water, lifting wet heavy clothes, line drying and hours of tedious ironing. Although done less frequently than we do laundry today, this was not out of frugality as much as exhaustion. Efficient homes required all occupants to rinse out their small things each evening, but eventually everything would need a good washing. In 1887, there were two laundries in town offering services. To sweeten the deal, the Exeter Steam Laundry began offering free pick up and delivery in 1897. Other laundries quickly opened with the same services. “Our collecting days Mondays and Thursdays,” advertised the Steam Laundry, “call cards have been distributed, others can have them on application.”

Housewives took to the delivery system with enthusiasm. Lists were sent to merchants via small children or by postal card. Mail was delivered several times each day – another service that expanded in previous years only to contract later. Ice was ordered by placing a sign in the window. The ice wagon would arrive at its own pace, servicing the customers along his route. Milk carts, like ice wagons, delivered to regular customers. People who had milk delivered often contracted with individual farmers. There were no dairies advertising until the 1920s. The sanitary milk bottle was not invented until the late 1880s and wasn’t in common use until the 1890s. Before that, a farmer would deliver milk from open cans using a dipper to dispense the required amount into a housewife’s pitcher. After the 1920s when milk was considered safe and sanitary thanks to pasteurization and modern bottling, milk delivery (as well as consumption) went way up.

There were fewer bakeries in the 1880s. Most people did the bulk of their everyday baking at home. The convenience of bread delivery arrived after the turn of the century. Like dairies, bakeries offered delivery direct from the business with no showroom needed.

The heydays of home delivery were the early decades of the twentieth century. When telephones were introduced, it was the local merchants who became early adopters. By the time, the 1911 directory was published, no grocer was foolish enough to advertise without mentioning telephone ordering. The convenience to a housewife on Washington Street to simply dial the grocer, order meats, canned vegetables and maybe something she’d seen advertised (“Moxie – Nerve Food – Refreshes, strengthens, is healthful and nourishes worn-out nerves of mind and body, this great temperance beverage – Your grocer will take it to your house!” Order it by name!), must have seemed very modern. Milk was delivered daily, bread several times each week. The fish wagon arrived once a week. Higgins Ice Cream delivered “at short notice” lest the product melt.

And if you chipped a glass, burned the frying pan or needed a new wash tub, there was always the Sears and Roebuck or Montgomery Ward catalog. They were the Amazon of their day – undercutting local dealers and allowing the customer to browse through the merchandise from the comfort of home, and everything was shipped right to the house.

If all this sounds like the perfect system for surviving a quarantine, keep in mind that, despite all this convenience, the state of medicine at the time was scary. Few vaccinations, no antibiotics, rampant tuberculosis, measles, mumps, influenza, chicken pox. A blister could kill you. All the more reason to stay at home. Stay at home. We’ll get through this.

Barbara Rimkunas is curator of the Exeter Historical Society. Support the Exeter Historical Society by becoming a member! Join online at: www.exeterhistory.org

Image: Goodwin Brothers Grocers on Water Street in Exeter pose with their delivery wagon, c. 1900.

Comments