The Shipbuilding Legacy of an Exeter Neighborhood

by Barbara Rimkunas

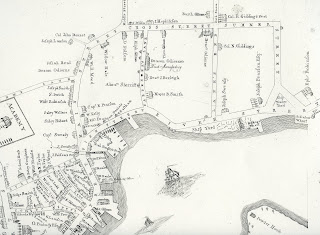

This "Historically Speaking" column was published in the Exeter News-Letter on Friday, February 2, 2018. In 1802, Phineas Merrill laid out the earliest accurate maps of the town of Exeter. One of the maps shows the entire town with its boundaries, waterways and roads. The other is a map of "the Compact Part of the Town of Exeter" or what was commonly referred to as "Exeter Village." Today we might call this the Exeter downtown. Encompassing the area roughly from Great Bridge to Swasey Parkway, the map shows us not only where the major commercial and municipal part of town was located, but also a glimpse into the town's economy during the period following the Revolution.

Exeter's main source of income before the Revolution was lumber. The British navy needed lumber for use as masts and spars. New Hampshire's towering white pine was perfect for this need. But along with shipping masts and sawed lumber, the abundance of wood was perfect for ship building. Exeter produced ships as early as the 1650s. It might surprise some that a seemingly inland town as Exeter might be home to a ship building industry, but it was far easier (and cheaper) to build a ship close to where the lumber was located. The costs of transporting wood all the way to British ship builders was problematic. Ship building flourished in Exeter and Portsmouth up until the Revolution. Lumber was brought to town from Brentwood and Epping, traveling down Epping Road to today's Park Street - which was at one time called "Mast Way" and later "Lane's End." There, it was either shipped to market or used to make ships.

Charles Bell, our venerable town historian of the nineteenth century, wrote of the waterfront, "From the lower falls down as far as meeting-house hill on the west side of the river, ship and lumber-yards stretched almost continuously between the stores and wharves. On the streets, a little way back, were blacksmith shops, where the roar of the forge and the ringing blows of the hammer were heard from morning till night, making a fitting accompaniment to the sounds of the shipwrights adze and the caulker's mallet which arose from the hulls propped up on the ways, waiting the hour when they should take their plunge into the element for which they were destined." It's a pleasing scene, although it barely made it through the Revolutionary era. When trade between the US and Great Britain shut down, shipbuilding slowed to a trickle. In part, this was because it was difficult for local firms to obtain all of the necessary components needed to fully rig a ship. After Independence, locally sourced iron, rope and canvas were sorely needed.

Merrill's 1802 map has a curious feature on a street called "Carpenter's Lane." This particular section of map, in the upper right quadrant, is the heart of Exeter's shipbuilding industry. The very name "Carpenter's Lane" indicates the livelihood of its residents. On that street, that we know today as Green Street, there is a long building labeled "Deacon Odiorne's Duck Manufactory" with the latter part written in an elegant type unlike any other used on the map. Before you start wondering why anyone would be making wooden decoy ducks, in this use "duck" is a type of canvas used for sailcloth. William Saltonstall noted in his, Ports of Piscataqua, "In February, 1789, the New Hampshire Gazette mentioned the passage of a state law 'to encourage the erecting of proper bildings for carrying on the manufacture of sail cloth or duck, within this state.' Two months later local farmers were urged to pay special attention to the culture of flax." He continues, "in September, 1790, duck of the best quality was offered for sale at the manufactory in Exeter. The various grades of duck from one to six were available on moderate terms for cash, flax or West India goods. Deacon Odiorne's mill employed about eight spinners of warp and about the same number of weavers. The weft was spun in private homes." Duck manufacturing was a subsidized industry, earning a bounty of seven shillings per bolt produced. These payments were stopped in 1796 and Odiorne sold his factory to new investors. At the time Merrill made his map, its likely Odiorne no longer owned it, but the town still knew it as "Deacon Odiorne's Duck Manufactory" and it was still a source of pride.

Just north of Carpenter's Lane, Merrill's map indicates the location of one of the last shipyards in Exeter. Today it would be roughly located at the base of Park Street on the western shore of the Squamscott River. There is no trace of the shipyard today - the shoreline of the river has been altered by infilling to create Swasey Parkway. Ambrose Swasey probably knew, when he financed the parkway in 1930, that one of his ancestors, Joseph Swasey, had established his shipyard on that location as early as 1800. Swasey was one of the busiest shipbuilders in town. On Merrill's map, his house is located directly across the street from the shipyard. Swasey may have been learning his trade when Ephraim Robinson and Eliphalet Giddings constructed the largest vessel ever built in Exeter. The Hercules was a 500 ton monster when compared to the average 250 ton ships constructed on the Squamscott. Saltonstall tells us, "the fact that her keel was laid parallel to the channel of the river suggests that she was launched sideways." Charles Bell, writing in 1888, noted "one who recently deceased, used to describe a large vessel of probably five hundred tons that he saw on the stocks, the bowsprit of which projected beyond the fronts of the adjacent buildings, into Water Street, between Spring and Center streets. A vessel of that size had so great a draft of water that it had to be buoyed up by empty hogsheads in order to pass down the river at ordinary tide."

Barbara Rimkunas is curator of the Exeter Historical Society. Her column appears every other Friday and she may be reached at info@exeterhistory.org.

Image: Details on the 1802 Phineas Merrill Map of Exeter indicate the shipbuilding industry was still thriving. The shipbuilding industry in New England thrived from the seventeenth century until the mid-nineteenth.

This "Historically Speaking" column was published in the Exeter News-Letter on Friday, February 2, 2018. In 1802, Phineas Merrill laid out the earliest accurate maps of the town of Exeter. One of the maps shows the entire town with its boundaries, waterways and roads. The other is a map of "the Compact Part of the Town of Exeter" or what was commonly referred to as "Exeter Village." Today we might call this the Exeter downtown. Encompassing the area roughly from Great Bridge to Swasey Parkway, the map shows us not only where the major commercial and municipal part of town was located, but also a glimpse into the town's economy during the period following the Revolution.

Exeter's main source of income before the Revolution was lumber. The British navy needed lumber for use as masts and spars. New Hampshire's towering white pine was perfect for this need. But along with shipping masts and sawed lumber, the abundance of wood was perfect for ship building. Exeter produced ships as early as the 1650s. It might surprise some that a seemingly inland town as Exeter might be home to a ship building industry, but it was far easier (and cheaper) to build a ship close to where the lumber was located. The costs of transporting wood all the way to British ship builders was problematic. Ship building flourished in Exeter and Portsmouth up until the Revolution. Lumber was brought to town from Brentwood and Epping, traveling down Epping Road to today's Park Street - which was at one time called "Mast Way" and later "Lane's End." There, it was either shipped to market or used to make ships.

Charles Bell, our venerable town historian of the nineteenth century, wrote of the waterfront, "From the lower falls down as far as meeting-house hill on the west side of the river, ship and lumber-yards stretched almost continuously between the stores and wharves. On the streets, a little way back, were blacksmith shops, where the roar of the forge and the ringing blows of the hammer were heard from morning till night, making a fitting accompaniment to the sounds of the shipwrights adze and the caulker's mallet which arose from the hulls propped up on the ways, waiting the hour when they should take their plunge into the element for which they were destined." It's a pleasing scene, although it barely made it through the Revolutionary era. When trade between the US and Great Britain shut down, shipbuilding slowed to a trickle. In part, this was because it was difficult for local firms to obtain all of the necessary components needed to fully rig a ship. After Independence, locally sourced iron, rope and canvas were sorely needed.

Merrill's 1802 map has a curious feature on a street called "Carpenter's Lane." This particular section of map, in the upper right quadrant, is the heart of Exeter's shipbuilding industry. The very name "Carpenter's Lane" indicates the livelihood of its residents. On that street, that we know today as Green Street, there is a long building labeled "Deacon Odiorne's Duck Manufactory" with the latter part written in an elegant type unlike any other used on the map. Before you start wondering why anyone would be making wooden decoy ducks, in this use "duck" is a type of canvas used for sailcloth. William Saltonstall noted in his, Ports of Piscataqua, "In February, 1789, the New Hampshire Gazette mentioned the passage of a state law 'to encourage the erecting of proper bildings for carrying on the manufacture of sail cloth or duck, within this state.' Two months later local farmers were urged to pay special attention to the culture of flax." He continues, "in September, 1790, duck of the best quality was offered for sale at the manufactory in Exeter. The various grades of duck from one to six were available on moderate terms for cash, flax or West India goods. Deacon Odiorne's mill employed about eight spinners of warp and about the same number of weavers. The weft was spun in private homes." Duck manufacturing was a subsidized industry, earning a bounty of seven shillings per bolt produced. These payments were stopped in 1796 and Odiorne sold his factory to new investors. At the time Merrill made his map, its likely Odiorne no longer owned it, but the town still knew it as "Deacon Odiorne's Duck Manufactory" and it was still a source of pride.

Just north of Carpenter's Lane, Merrill's map indicates the location of one of the last shipyards in Exeter. Today it would be roughly located at the base of Park Street on the western shore of the Squamscott River. There is no trace of the shipyard today - the shoreline of the river has been altered by infilling to create Swasey Parkway. Ambrose Swasey probably knew, when he financed the parkway in 1930, that one of his ancestors, Joseph Swasey, had established his shipyard on that location as early as 1800. Swasey was one of the busiest shipbuilders in town. On Merrill's map, his house is located directly across the street from the shipyard. Swasey may have been learning his trade when Ephraim Robinson and Eliphalet Giddings constructed the largest vessel ever built in Exeter. The Hercules was a 500 ton monster when compared to the average 250 ton ships constructed on the Squamscott. Saltonstall tells us, "the fact that her keel was laid parallel to the channel of the river suggests that she was launched sideways." Charles Bell, writing in 1888, noted "one who recently deceased, used to describe a large vessel of probably five hundred tons that he saw on the stocks, the bowsprit of which projected beyond the fronts of the adjacent buildings, into Water Street, between Spring and Center streets. A vessel of that size had so great a draft of water that it had to be buoyed up by empty hogsheads in order to pass down the river at ordinary tide."

Barbara Rimkunas is curator of the Exeter Historical Society. Her column appears every other Friday and she may be reached at info@exeterhistory.org.

Image: Details on the 1802 Phineas Merrill Map of Exeter indicate the shipbuilding industry was still thriving. The shipbuilding industry in New England thrived from the seventeenth century until the mid-nineteenth.

Comments