Somewhere in France: (part 1)

by Barbara Rimkunas

This "Historically Speaking" column was published in the Exeter News-Letter on Friday, March 2, 2018.

"Well, mother, your six-foot son is alive and feeling fine after five days in the front line," wrote Sergeant Frank Dwyer on March 4, 1918. Whether this produced comfort or concern to his mother, we do not know. Having a family member in harm's way was stressful and any news was generally welcome. During World War I, the Exeter News-Letter published letters from soldiers in nearly every edition. The young men who wrote home did so with a mixture of wit and naivete. This was the greatest adventure of their lives and they generally attempted to make that clear.

Exeter's soldiers began writing during training. Lieutenant Kenneth Fuller was grateful that he'd had camping experience as a boy when he had to endure some miserable days at Camp Greene in Charlotte, North Carolina. An icy storm hit the camp in January of 1918. "I went down and looked in the tents and found most of them perfect quagmires and some with small torrents running through. The men could not make their cots set level. They were sitting on them to keep out of the mud, shivering and in many cases cheerfully making the most of it, but in others complaining miserably." His own tent suffered flooding and he piled all his possessions onto his bunk to keep things dry. "I told the men, (to cheer them up?), I'll bet they never have a harder night in France. I hardly slept a wink all night. The rain and wind rattled and shook the tent so that I thought the thing would blow away."

"George," described as a "Dow's Hill boy in the Navy" wrote a homesick note to his father to assure him he was not homesick. "I am not homesick at all, although you know I think the United States and home is the best place on earth. I never spent a happier two months than the last two, because it is what I want. I know you are glad I am here. A little lump does come up in my throat when I open a package from mother, just as it used to when I got something from home when at college or I opened the lunch she put up for me to take to school. That is because I know I have the best mother in the world." He sounds fine.

Lewis Swain, a musician by training, surprised everyone including himself by winning a marksmanship award. "I was up against a lot of old army men (non coms and officers) who wear medals for marksmen, sharpshooters and expert riflemen, and through some hook or crook I beat them all." "You can tell Uncle George," he added, "that my early training in handling a gun under him and Uncle Bert came in pretty handy last week and I guess he won't be disappointed in me when he hears that I showed up a few old timers at the game."

Arrival overseas brought the reality of war into the letters. Private Howard Hobbs of Hampton wrote from "somewhere in France," "you ought to see the ground around here; literally every foot is torn up by shells, not an inch (no exaggeration) is left untouched. Everything for miles around is bleak and devastated. Not a live tree is standing. Nearest towns are in ruins and uninhabited." His days, he said, were filled with, "digging our own gun pits, dugouts, communication trenches, etc.; in fact getting ready for the guns to be put into position."

J. Wilton Peters, a graduate of Phillips Exeter Academy, wrote to his Exeter friend, Dr. William Nute: "Everything went fine until the following morning at 5:30 when I awoke to the tune of grenades and machine guns going off at such rapidity that it was hard to distinguish which was which. Then for the first time, I knew why I was there. If you have never been under heavy shell fire you can't imagine the feeling that grips one. I won't say I wasn't scared to death, because I'd be the biggest liar on the earth if I did." A shell landed seven feet away from Peters, narrowly missing his friends. "Well, Doc., why in the world that shell didn't explode I don't know. Of all the shells that landed during the next 45 minutes that was the only one that didn't explode. It still sticks in that wall and as far as I'm concerned it will remain there till Kingdom Come." He raced from the trench with other men eventually following a French soldier into a cellar hole. "To make things worse I lost my gas mask in the rush and to wait there expecting some gas shells at any moment didn't add to my comfort. At intervals of 10 or 15 minutes it would seem to let up and then bang away it would go again and you could hear a piece of the roof come tumbling down - thoughts of being buried alive in that cave. After an hour it let up and we slipped over to the other boys. We found them O.K. One shell exploded on top of their 'abri,' but didn't go through. Well, Doc, after a more thorough examination of the surroundings I came to the conclusion that the Germans can shoot high explosive shells better than I can. Out of 125 shells, not one fell outside of a radius of 50 to 75 yards. If you can tell me why that shell didn't explode, I'll tell you when the war's going to end." He ended his letter, "Best of luck and love to all the family. Never felt better in my life."

Barbara Rimkunas is curator of the Exeter Historical Society. Her column appears every other Friday and she may be reached at info@exeterhistory.org.

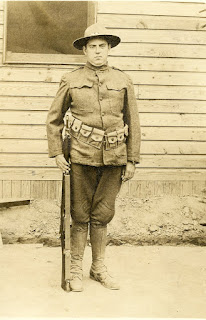

Image: Private Michael J. Broderick of Exeter, who enlisted on April 26, 1918, sent this photo home from training at Camp Hancock, Georgia.

This "Historically Speaking" column was published in the Exeter News-Letter on Friday, March 2, 2018.

"Well, mother, your six-foot son is alive and feeling fine after five days in the front line," wrote Sergeant Frank Dwyer on March 4, 1918. Whether this produced comfort or concern to his mother, we do not know. Having a family member in harm's way was stressful and any news was generally welcome. During World War I, the Exeter News-Letter published letters from soldiers in nearly every edition. The young men who wrote home did so with a mixture of wit and naivete. This was the greatest adventure of their lives and they generally attempted to make that clear.

Exeter's soldiers began writing during training. Lieutenant Kenneth Fuller was grateful that he'd had camping experience as a boy when he had to endure some miserable days at Camp Greene in Charlotte, North Carolina. An icy storm hit the camp in January of 1918. "I went down and looked in the tents and found most of them perfect quagmires and some with small torrents running through. The men could not make their cots set level. They were sitting on them to keep out of the mud, shivering and in many cases cheerfully making the most of it, but in others complaining miserably." His own tent suffered flooding and he piled all his possessions onto his bunk to keep things dry. "I told the men, (to cheer them up?), I'll bet they never have a harder night in France. I hardly slept a wink all night. The rain and wind rattled and shook the tent so that I thought the thing would blow away."

"George," described as a "Dow's Hill boy in the Navy" wrote a homesick note to his father to assure him he was not homesick. "I am not homesick at all, although you know I think the United States and home is the best place on earth. I never spent a happier two months than the last two, because it is what I want. I know you are glad I am here. A little lump does come up in my throat when I open a package from mother, just as it used to when I got something from home when at college or I opened the lunch she put up for me to take to school. That is because I know I have the best mother in the world." He sounds fine.

Lewis Swain, a musician by training, surprised everyone including himself by winning a marksmanship award. "I was up against a lot of old army men (non coms and officers) who wear medals for marksmen, sharpshooters and expert riflemen, and through some hook or crook I beat them all." "You can tell Uncle George," he added, "that my early training in handling a gun under him and Uncle Bert came in pretty handy last week and I guess he won't be disappointed in me when he hears that I showed up a few old timers at the game."

Arrival overseas brought the reality of war into the letters. Private Howard Hobbs of Hampton wrote from "somewhere in France," "you ought to see the ground around here; literally every foot is torn up by shells, not an inch (no exaggeration) is left untouched. Everything for miles around is bleak and devastated. Not a live tree is standing. Nearest towns are in ruins and uninhabited." His days, he said, were filled with, "digging our own gun pits, dugouts, communication trenches, etc.; in fact getting ready for the guns to be put into position."

J. Wilton Peters, a graduate of Phillips Exeter Academy, wrote to his Exeter friend, Dr. William Nute: "Everything went fine until the following morning at 5:30 when I awoke to the tune of grenades and machine guns going off at such rapidity that it was hard to distinguish which was which. Then for the first time, I knew why I was there. If you have never been under heavy shell fire you can't imagine the feeling that grips one. I won't say I wasn't scared to death, because I'd be the biggest liar on the earth if I did." A shell landed seven feet away from Peters, narrowly missing his friends. "Well, Doc., why in the world that shell didn't explode I don't know. Of all the shells that landed during the next 45 minutes that was the only one that didn't explode. It still sticks in that wall and as far as I'm concerned it will remain there till Kingdom Come." He raced from the trench with other men eventually following a French soldier into a cellar hole. "To make things worse I lost my gas mask in the rush and to wait there expecting some gas shells at any moment didn't add to my comfort. At intervals of 10 or 15 minutes it would seem to let up and then bang away it would go again and you could hear a piece of the roof come tumbling down - thoughts of being buried alive in that cave. After an hour it let up and we slipped over to the other boys. We found them O.K. One shell exploded on top of their 'abri,' but didn't go through. Well, Doc, after a more thorough examination of the surroundings I came to the conclusion that the Germans can shoot high explosive shells better than I can. Out of 125 shells, not one fell outside of a radius of 50 to 75 yards. If you can tell me why that shell didn't explode, I'll tell you when the war's going to end." He ended his letter, "Best of luck and love to all the family. Never felt better in my life."

Barbara Rimkunas is curator of the Exeter Historical Society. Her column appears every other Friday and she may be reached at info@exeterhistory.org.

Image: Private Michael J. Broderick of Exeter, who enlisted on April 26, 1918, sent this photo home from training at Camp Hancock, Georgia.

Comments