The Steam Gristmill

by Barbara Rimkunas

This "Historically Speaking" column was published by the Exeter News-Letter on Friday, May 20, 2016.

At one time, Exeter could boast ten gristmills. This type of mill, which produced flour, was so vitally important to the English who settled here that it was the first mill erected at the falls in the center of town. Historian Charles Bell explains, “The first mill in the town was for grinding grain, and was built by Thomas Wilson at the foot of the main falls on the easterly side of the island now reached by String bridge, near where a similar mill stands to this day (1888 – when Bell was writing his History of Exeter, New Hampshire). The mill site and the island, on which Wilson also erected his house, were granted to him by the town, probably in the very first season of their occupation, and before any formal records that we know of were kept.”

A gristmill was important to Englishmen. Their basic diet was bread, ale, cabbage, peas and a bit of meat. The native population made cornmeal cakes, grinding the corn into meal using a mortar and pestle. But the new settlers found this method to be cumbersome. Olive Tardiff, in her book Exeter Squamscott: River of Many Uses, explains the rush to build a gristmill: “Grinding by hand was much too time-consuming for the hewers of logs and builders of homes. A gristmill could free busy hands for more important work.”

Wilson, and later his heirs, functioned as the town’s only gristmill until 1670, when enterprising John Gilman decided to get in on the action and set up his mill on the opposite side of the falls. The townsmen must have felt that Gilman’s mill was superior to the old Wilson mill because they voted to, “give all the right the town have in the stream and island to Captain John Gilman, where the said Gilman’s corn-mill now stands, with privilege for a bridge to go on to the island; and the abovesaid John Gilman doth oblige himself to grind the inhabitants’ corn when wanted, for two quarts in every bushel.” Millers worked for shares. Cornmeal and flour were very marketable, so this was a good deal for Gilman. Travelers through Exeter, including George Washington, mention 10 gristmills along the Exeter River before 1800.

Most likely, the early Exeter gristmills were primarily grinding corn, although it can be difficult to tell from the records. Englishmen used the word ‘corn’ to mean any type of grain, but maize or Indian corn was locally the most successful crop. Within a few years of settlement, they would branch out to grow rye, wheat and barley. Barley was needed for the production of ale and beer. Rye flour was used with cornmeal to create the most common bread, usually called ‘rye ‘n’ injun,’ which was eaten all across New England. If we traveled back in time to the 18th century we’d discover the bread to be darker, heavier and chewier than any we’re used to today. On the whole, it was quite healthy.

The Phineas Merrill map of 1802 – our earliest accurate map of the town – shows four gristmills clustered around the falls in the center of town. Their location at the falls indicates that all are using water power. Even the gristmill mentioned by Charles Bell in 1888 is on the river. But sometime before Bell wrote his history, Exeter had its first steam powered gristmill.

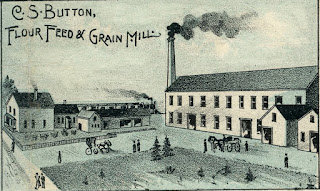

First appearing on the 1874 map on Arbor Street, the steam gristmill doesn’t list an owner. Placed by the B&M depot, the business was well-placed for modern transportation of both raw material and finished product. But somehow, it didn’t prosper. In 1889, the Exeter News-Letter remarked that, “the project is discussed of organizing a company with almost $1200 of capital for the purchase and operation of a long disused steam grist mill. Well managed, the business would pay good return.” Within three months they could announce, “The entire plant was purchased by Francis Hilliard Esq. of Kensington. He has associated himself with Mr. C.S. Button, senior member of Button Brothers who will run the mill.” The Button Brothers bakery was a thriving business on Union Street. It was no wonder one of the brothers would be interested in milling flour. Improvements were made and the mill reported a year later that, “business is steadily increasing, a new roller mill now being introduced will greatly cheapen the cost of production and enable the firm to do wholesale business to better advantage.” Christian Button would remain the mill manager until it was sold to William Jenkins in 1897.

Primarily a wholesale dealer, Jenkins expanded to become a dealer in hay, grain, straw and feed. A business directory from 1907 declared that, “it requires 150 carloads of grain annually to meet the requirements of their trade. Special features are made of White Witch and White Lily flours. These brands have come to be recognized in this vicinity as the leaders in the flour trade.” White Lily flour is still popular today in the southern parts of the United States, although it cannot be found (or is difficult to find) in New England. W.M. Jenkins closed up for good in 1924. The buildings were later used by the Rockingham Farmers Exchange and later the Merrimack Farmers Exchange, which existed as a farmer’s collective until an embezzlement scandal in 1982 closed it down. The Merrimack Farmers Exchange was later purchased by Blue Seal. By that time, it was no longer functioning as a gristmill. Exeter’s founding mechanical industry was no longer needed.

Images: C.S. Button’s steam gristmill – taken from the 1896 Birdseye Map of Exeter (an illustration) and Jenkin’s steam gristmill – from a 1907 Business Guide to Exeter (a photo, admittedly quite fuzzy and dotty). It should be noted that these are the same gristmill on Arbor Street. Only the owners changed.

This "Historically Speaking" column was published by the Exeter News-Letter on Friday, May 20, 2016.

At one time, Exeter could boast ten gristmills. This type of mill, which produced flour, was so vitally important to the English who settled here that it was the first mill erected at the falls in the center of town. Historian Charles Bell explains, “The first mill in the town was for grinding grain, and was built by Thomas Wilson at the foot of the main falls on the easterly side of the island now reached by String bridge, near where a similar mill stands to this day (1888 – when Bell was writing his History of Exeter, New Hampshire). The mill site and the island, on which Wilson also erected his house, were granted to him by the town, probably in the very first season of their occupation, and before any formal records that we know of were kept.”

A gristmill was important to Englishmen. Their basic diet was bread, ale, cabbage, peas and a bit of meat. The native population made cornmeal cakes, grinding the corn into meal using a mortar and pestle. But the new settlers found this method to be cumbersome. Olive Tardiff, in her book Exeter Squamscott: River of Many Uses, explains the rush to build a gristmill: “Grinding by hand was much too time-consuming for the hewers of logs and builders of homes. A gristmill could free busy hands for more important work.”

Most likely, the early Exeter gristmills were primarily grinding corn, although it can be difficult to tell from the records. Englishmen used the word ‘corn’ to mean any type of grain, but maize or Indian corn was locally the most successful crop. Within a few years of settlement, they would branch out to grow rye, wheat and barley. Barley was needed for the production of ale and beer. Rye flour was used with cornmeal to create the most common bread, usually called ‘rye ‘n’ injun,’ which was eaten all across New England. If we traveled back in time to the 18th century we’d discover the bread to be darker, heavier and chewier than any we’re used to today. On the whole, it was quite healthy.

The Phineas Merrill map of 1802 – our earliest accurate map of the town – shows four gristmills clustered around the falls in the center of town. Their location at the falls indicates that all are using water power. Even the gristmill mentioned by Charles Bell in 1888 is on the river. But sometime before Bell wrote his history, Exeter had its first steam powered gristmill.

First appearing on the 1874 map on Arbor Street, the steam gristmill doesn’t list an owner. Placed by the B&M depot, the business was well-placed for modern transportation of both raw material and finished product. But somehow, it didn’t prosper. In 1889, the Exeter News-Letter remarked that, “the project is discussed of organizing a company with almost $1200 of capital for the purchase and operation of a long disused steam grist mill. Well managed, the business would pay good return.” Within three months they could announce, “The entire plant was purchased by Francis Hilliard Esq. of Kensington. He has associated himself with Mr. C.S. Button, senior member of Button Brothers who will run the mill.” The Button Brothers bakery was a thriving business on Union Street. It was no wonder one of the brothers would be interested in milling flour. Improvements were made and the mill reported a year later that, “business is steadily increasing, a new roller mill now being introduced will greatly cheapen the cost of production and enable the firm to do wholesale business to better advantage.” Christian Button would remain the mill manager until it was sold to William Jenkins in 1897.

Primarily a wholesale dealer, Jenkins expanded to become a dealer in hay, grain, straw and feed. A business directory from 1907 declared that, “it requires 150 carloads of grain annually to meet the requirements of their trade. Special features are made of White Witch and White Lily flours. These brands have come to be recognized in this vicinity as the leaders in the flour trade.” White Lily flour is still popular today in the southern parts of the United States, although it cannot be found (or is difficult to find) in New England. W.M. Jenkins closed up for good in 1924. The buildings were later used by the Rockingham Farmers Exchange and later the Merrimack Farmers Exchange, which existed as a farmer’s collective until an embezzlement scandal in 1982 closed it down. The Merrimack Farmers Exchange was later purchased by Blue Seal. By that time, it was no longer functioning as a gristmill. Exeter’s founding mechanical industry was no longer needed.

Images: C.S. Button’s steam gristmill – taken from the 1896 Birdseye Map of Exeter (an illustration) and Jenkin’s steam gristmill – from a 1907 Business Guide to Exeter (a photo, admittedly quite fuzzy and dotty). It should be noted that these are the same gristmill on Arbor Street. Only the owners changed.

Comments