The Settlement of Exeter

by Barbara Rimkunas

This "Historically Speaking" column appeared in the Exeter News-Letter on Friday, January 18, 2013.

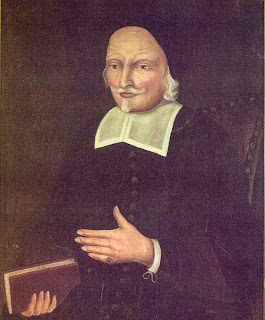

The earliest years of Exeter’s existence as a town must have been difficult. The Reverend John Wheelwright arrived here in March of 1638 traveling through deep snow. He’d been expelled the previous November from the Massachusetts Bay Colony for unorthodox preaching and wintered over in the wilderness of New Hampshire, most likely with Edward Hilton in the Dover area.

Wheelwright intended to stay and proposed creating a settlement at the falls of the Squamscott – a river and region so-named because of the seasonal Native People who lived there when warm weather approached. A deal was brokered with the Squamscotts and two deeds drawn up granting the English rights of ownership to the land while retaining the fishing, hunting and cultivation rights for the Natives. The agreement seemed to suit everyone involved and soon after, more Englishmen and their families arrived from Massachusetts to live in the new community.

New Hampshire, at that time, had no centralized government and for the first year of its existence, Exeter had no real government either. The people must have been far too busy building shelters, clearing land and getting in crops to worry about governance. By the next year, however, they decided to get organized. The first order of business was to apportion the land. A year’s worth of exploration had, no doubt, given them some familiarity with the landscape.

They began by giving each head of household some farmland – somewhere between 4 and 80 acres each depending on need and social status. The meadows were apportioned among those who had cattle and rules set for the use of the forests and rivers.

Relations with the Squamscotts remained fairly calm, although the two groups must have marveled at their differing ways of procuring food. The Natives came to Exeter in the Spring to fish in the river, gather berries and nuts and plant small crops such as corn and squash. Their meat – deer, pigeon, turkeys and squirrel – could be found in abundance in the dense forests that surrounded the town. Pigeons were so plentiful that it was said a flock alight could block out the sun.

The English, on the other hand, insisted on bread, beef and pork – none of which could be gathered from the environment without a great deal of effort. Grain crops required cleared land and some type of mill to produce flour. Cattle and swine had to be tended and fed. Within a few years, the townspeople assigned one person to tend the cattle each day. They were gathered in the center of town each morning and taken to the woods to forage. In the evenings, they were returned to their homes.

Pigs, however, were more problematic. They weren’t fed regular meals but were set loose each day to find their own food. As they rooted around for eatables, they sometimes destroyed local gardens. At a town meeting held in 1641 an Exeter goodman was required to “allow the Indians one bushel of corne for ye labor wch was spent by ym in replantying of yt corne of yrs wch was spoyld by his swine.” Loose pigs eventually led to strict laws regarding fences and the job of “inspector of fences” became an important task.

Everyone in town was granted the right to fish on the river, providing they did not infringe or destroy the Native fishing weirs. In 1644, Christopher Lawson was granted the right to construct a weir, which was a way of trapping fish, across the river. He was supposed to ensure that small boats and canoes could still get through, but it must not have worked out because the next year his grant was revoked and the rights of the river were extended back to all townsfolk.

Rights to the forests were also controlled by the town government. Within the first year the central part of the village was largely deforested and harvesting lumber was restricted to one half-mile outside of town. Since food production was low, lumber became the chief source of income for most residents.

Most early records indicate that lumber finished into barrel staves and boards became the currency used in town instead of cash. Most of the local economy functioned on a barter system – including the payment of taxes, which were argued over as much as they are today.

In this manner of inventing rules as they were needed and regulating behavior regarding resources, the small community held together during the early years. When food was scarce, the council ordered a general search of all homes and surplus food was divided among those who needed it – with the understanding that market price would be paid in exchange. The town thus avoided any of the ‘starving times’ experienced in earlier settlements like Plymouth or Jamestown. The laws changed within several decades after the Natives left and sawmills created a booming lumber industry, but the Town of Exeter began with seemingly humble gentlemen’s agreements.

The image above from the town records:

This "Historically Speaking" column appeared in the Exeter News-Letter on Friday, January 18, 2013.

The earliest years of Exeter’s existence as a town must have been difficult. The Reverend John Wheelwright arrived here in March of 1638 traveling through deep snow. He’d been expelled the previous November from the Massachusetts Bay Colony for unorthodox preaching and wintered over in the wilderness of New Hampshire, most likely with Edward Hilton in the Dover area.

Wheelwright intended to stay and proposed creating a settlement at the falls of the Squamscott – a river and region so-named because of the seasonal Native People who lived there when warm weather approached. A deal was brokered with the Squamscotts and two deeds drawn up granting the English rights of ownership to the land while retaining the fishing, hunting and cultivation rights for the Natives. The agreement seemed to suit everyone involved and soon after, more Englishmen and their families arrived from Massachusetts to live in the new community.

New Hampshire, at that time, had no centralized government and for the first year of its existence, Exeter had no real government either. The people must have been far too busy building shelters, clearing land and getting in crops to worry about governance. By the next year, however, they decided to get organized. The first order of business was to apportion the land. A year’s worth of exploration had, no doubt, given them some familiarity with the landscape.

They began by giving each head of household some farmland – somewhere between 4 and 80 acres each depending on need and social status. The meadows were apportioned among those who had cattle and rules set for the use of the forests and rivers.

Relations with the Squamscotts remained fairly calm, although the two groups must have marveled at their differing ways of procuring food. The Natives came to Exeter in the Spring to fish in the river, gather berries and nuts and plant small crops such as corn and squash. Their meat – deer, pigeon, turkeys and squirrel – could be found in abundance in the dense forests that surrounded the town. Pigeons were so plentiful that it was said a flock alight could block out the sun.

The English, on the other hand, insisted on bread, beef and pork – none of which could be gathered from the environment without a great deal of effort. Grain crops required cleared land and some type of mill to produce flour. Cattle and swine had to be tended and fed. Within a few years, the townspeople assigned one person to tend the cattle each day. They were gathered in the center of town each morning and taken to the woods to forage. In the evenings, they were returned to their homes.

Pigs, however, were more problematic. They weren’t fed regular meals but were set loose each day to find their own food. As they rooted around for eatables, they sometimes destroyed local gardens. At a town meeting held in 1641 an Exeter goodman was required to “allow the Indians one bushel of corne for ye labor wch was spent by ym in replantying of yt corne of yrs wch was spoyld by his swine.” Loose pigs eventually led to strict laws regarding fences and the job of “inspector of fences” became an important task.

Everyone in town was granted the right to fish on the river, providing they did not infringe or destroy the Native fishing weirs. In 1644, Christopher Lawson was granted the right to construct a weir, which was a way of trapping fish, across the river. He was supposed to ensure that small boats and canoes could still get through, but it must not have worked out because the next year his grant was revoked and the rights of the river were extended back to all townsfolk.

Rights to the forests were also controlled by the town government. Within the first year the central part of the village was largely deforested and harvesting lumber was restricted to one half-mile outside of town. Since food production was low, lumber became the chief source of income for most residents.

Most early records indicate that lumber finished into barrel staves and boards became the currency used in town instead of cash. Most of the local economy functioned on a barter system – including the payment of taxes, which were argued over as much as they are today.

In this manner of inventing rules as they were needed and regulating behavior regarding resources, the small community held together during the early years. When food was scarce, the council ordered a general search of all homes and surplus food was divided among those who needed it – with the understanding that market price would be paid in exchange. The town thus avoided any of the ‘starving times’ experienced in earlier settlements like Plymouth or Jamestown. The laws changed within several decades after the Natives left and sawmills created a booming lumber industry, but the Town of Exeter began with seemingly humble gentlemen’s agreements.

The image above from the town records:

This entry in the Exeter Town Records is from April 9th, 1640. Reading early records can be difficult due to the style of handwriting, spelling variations and calendar differences – this entry begins: “An ordered & inacted law. It is inacted for a law constituted & made & consented unto by the whole assemblye at the Cort sollomly meet togeather in Exeter this 9 day of the 2 moneth Ano. 1640” The first month of the year was March, which explains why the entry was written in April – the second month of the year.

Comments