Influenza 1918

by Barbara Rimkunas

This "Historically Speaking" column appeared in the Exeter News-Letter on Tuesday, November 13, 2012.

This "Historically Speaking" column appeared in the Exeter News-Letter on Tuesday, November 13, 2012.

“We should surely remain calm and not lose our good sense,”

advised the New Hampshire State Board of Health, “We must have confidence that

our physicians and health officers, who have the real facts before them will

give the situation every consideration.” In the fall of 1918 the ‘situation’ at

hand was the arrival of a deadly world-wide influenza pandemic.

Individual cases of flu began to appear in Exeter in mid-September. School had been in session for only a few weeks and the newspapers were still full of news of the war. Although many newspapers suppressed information regarding the flu to prevent panic, the Exeter News-Letter began to run stories directly related to the outbreak in the last weeks of the month. By that time, it would have been difficult to ignore the flu’s grip on the town.

The 1918 influenza, sometimes called ‘Spanish Influenza,’ was caused by a quick spreading virus that could incapacitate its victims in hours. Some sufferers would slowly recover, others would develop deadly pneumonia and die within days – and the victims were generally people in the prime of life. Most flu epidemics preyed on the weakest members of society – the very old and the very young. This flu liked adults between the ages of 15 and 55.

On September 27th, the News-Letter reported, “The ‘Spanish Influenza,’ so-called, probably the grippe in severe form after a cycle of comparative mildness, has gained a strong foothold in Exeter. Hundreds are affected by severe colds, grippe and too many by pneumonia. To list its victims is impracticable. They are of all classes and ages and in instances entire families are affected. Manufactories, stores, and schools have their victims.” Exeter’s public schools stopped all classes. The Ioka was ordered closed by the Board of Health. The following week most clubs, churches and public meetings were postponed due to the flu. Phillips Exeter Academy continued to hold classes, fearing that sending the students home might only spread the disease, but the boys became sick and the gymnasium had to be converted into an infirmary.

There was no need to panic, the public was counseled, even though the Cottage Hospital was quickly overwhelmed with critical patients and much of the staff became ill. Dr. William Day fell victim and his slow recovery kept him from treating his patients. Not that there was much that could be done for flu victims. Even today there is little but supportive care that can be done for those suffering from influenza.

By the first week in October the death toll became a daily feature in the obituary columns. Boston postmaster William Murray died. Democratic Congressional candidate Edward Cummings died. And well-loved townspeople died.

“Mr. Charles B. Edgerly, superintendent of lines for the Exeter & Hampton Electric Company , and Miss Marion I. Fogg, of Hampton Falls, long a clerk in its office were married here last Saturday by Rev. John W. Savage, of Seabrook. It was necessarily a simple wedding, the bride then being affected by the influenza. Her condition since failed and early in the week she was compelled to enter the hospital, where she died last night of pneumonia.”

So many people died during the week of October 4th that the News-Letter headed an entire column, “Deaths from Pneumonia.” Immigrants, like 33 year old Stanislaus Yankowskas, a shoe-worker, died as quickly as wealthy high-born people. The Kent family, owners of the Exeter Manufacturing Company, lost their eldest son, Robert, who, like Yankowskas, was 33 years old. Robert Kent had been slated to take over management of the mill. His death left the job to his widowed mother, Adelaide.

No family in Exeter suffered as much as the Tewhill family of Garfield Street. A tight-knit Irish family, the Tewhills lost three family members to the flu. At one point during the epidemic there were five gravely ill people in the household, leaving the remaining two as caretakers. Stories such as this trickled in from all parts of the country. The death toll in Exeter was thought to be around 25 but might have been higher if you count those who died of pneumonia just before or just after the height of the epidemic.

After the terrible month of October the town began a slow recovery. Schools re-opened in the first week of November. The Exeter Public Library graciously provided amnesty for any overdue book fines for books checked out after September 21st. Reports changed from obituary notices to those of recovery. “Chief (of police) Elvyn A. Bunker resumed his duties on Monday after a long sickness from the influenza,” chirped the News-Letter on October 25th. “We seem to be passing from out the shadow of the pestilence, and there is a marked decrease in the number of new cases. Many who have been seriously ill are now nearing recovery.”

As hopeful rumors of a possible armistice in Europe began to surface in town, no news was received as joyfully in the tired town as this: “Miss Ellen Tewhill, who has been so seriously ill, on Tuesday walked from her Garfield Street home down town and back.”

Photo:

Individual cases of flu began to appear in Exeter in mid-September. School had been in session for only a few weeks and the newspapers were still full of news of the war. Although many newspapers suppressed information regarding the flu to prevent panic, the Exeter News-Letter began to run stories directly related to the outbreak in the last weeks of the month. By that time, it would have been difficult to ignore the flu’s grip on the town.

The 1918 influenza, sometimes called ‘Spanish Influenza,’ was caused by a quick spreading virus that could incapacitate its victims in hours. Some sufferers would slowly recover, others would develop deadly pneumonia and die within days – and the victims were generally people in the prime of life. Most flu epidemics preyed on the weakest members of society – the very old and the very young. This flu liked adults between the ages of 15 and 55.

On September 27th, the News-Letter reported, “The ‘Spanish Influenza,’ so-called, probably the grippe in severe form after a cycle of comparative mildness, has gained a strong foothold in Exeter. Hundreds are affected by severe colds, grippe and too many by pneumonia. To list its victims is impracticable. They are of all classes and ages and in instances entire families are affected. Manufactories, stores, and schools have their victims.” Exeter’s public schools stopped all classes. The Ioka was ordered closed by the Board of Health. The following week most clubs, churches and public meetings were postponed due to the flu. Phillips Exeter Academy continued to hold classes, fearing that sending the students home might only spread the disease, but the boys became sick and the gymnasium had to be converted into an infirmary.

There was no need to panic, the public was counseled, even though the Cottage Hospital was quickly overwhelmed with critical patients and much of the staff became ill. Dr. William Day fell victim and his slow recovery kept him from treating his patients. Not that there was much that could be done for flu victims. Even today there is little but supportive care that can be done for those suffering from influenza.

By the first week in October the death toll became a daily feature in the obituary columns. Boston postmaster William Murray died. Democratic Congressional candidate Edward Cummings died. And well-loved townspeople died.

“Mr. Charles B. Edgerly, superintendent of lines for the Exeter & Hampton Electric Company , and Miss Marion I. Fogg, of Hampton Falls, long a clerk in its office were married here last Saturday by Rev. John W. Savage, of Seabrook. It was necessarily a simple wedding, the bride then being affected by the influenza. Her condition since failed and early in the week she was compelled to enter the hospital, where she died last night of pneumonia.”

So many people died during the week of October 4th that the News-Letter headed an entire column, “Deaths from Pneumonia.” Immigrants, like 33 year old Stanislaus Yankowskas, a shoe-worker, died as quickly as wealthy high-born people. The Kent family, owners of the Exeter Manufacturing Company, lost their eldest son, Robert, who, like Yankowskas, was 33 years old. Robert Kent had been slated to take over management of the mill. His death left the job to his widowed mother, Adelaide.

No family in Exeter suffered as much as the Tewhill family of Garfield Street. A tight-knit Irish family, the Tewhills lost three family members to the flu. At one point during the epidemic there were five gravely ill people in the household, leaving the remaining two as caretakers. Stories such as this trickled in from all parts of the country. The death toll in Exeter was thought to be around 25 but might have been higher if you count those who died of pneumonia just before or just after the height of the epidemic.

After the terrible month of October the town began a slow recovery. Schools re-opened in the first week of November. The Exeter Public Library graciously provided amnesty for any overdue book fines for books checked out after September 21st. Reports changed from obituary notices to those of recovery. “Chief (of police) Elvyn A. Bunker resumed his duties on Monday after a long sickness from the influenza,” chirped the News-Letter on October 25th. “We seem to be passing from out the shadow of the pestilence, and there is a marked decrease in the number of new cases. Many who have been seriously ill are now nearing recovery.”

As hopeful rumors of a possible armistice in Europe began to surface in town, no news was received as joyfully in the tired town as this: “Miss Ellen Tewhill, who has been so seriously ill, on Tuesday walked from her Garfield Street home down town and back.”

Photo:

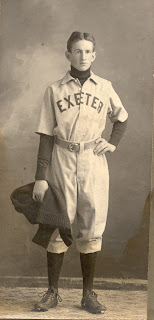

Robert Kent, seen here as a student at Phillips Exeter

Academy in 1905, died of influenza in November of 1918 at the age of 33. The

Kent family owned and managed the Exeter Manufacturing Company. His death left

management of the factory to his widowed mother, Adelaide.

Comments