The Problem of Tramps

by Barbara Rimkunas

This "Historically Speaking" column was published by the Exeter News-Letter on Friday, November 6, 2015.

“Tuesday night was the first of the winter in which no tramps sought shelter at Exeter’s Police Station,” the Exeter News-Letter noted in January of 1897. Wandering vagrants had always been a problem in towns along the railroad line, but the number of such people increased in the 1890s. Some towns erected small ‘tramp houses’ to accommodate – and incarcerate – people overnight. A bed and perhaps a meal would be exchanged for a small odd-job, such as cutting firewood, and then the tramps would be escorted out of town in the morning.

There is a romantic view of life lived in the rough. Bart Kennedy wrote of his tramping days at the turn of the century in A Man Adrift. “It may be that you feel the sense of freedom that comes from a total lack of responsibility. No one is dependent upon you. No one is waiting for you. If people have contempt for you, at least they leave you alone. And this is something.” Most men – and tramps were generally single men – took to the wandering life after an economic downturn. The Panic of 1893, what we would today call a recession, threw men out of work in many industrial cities. Factory workers found themselves without jobs and with no social support system. In New England, textile workers were often the ones left without jobs. Mills, including the Exeter Manufacturing Company, thought nothing of shutting down for weeks or months to conserve funds, leaving employees with no means of support. “To be penniless and on tramp is a curious experience,” Kennedy observed, “It may have been that at one time in your life you would have thought it impossible for you to beg. You would have shuddered at the bare idea. How shameful! You would have thought death would be preferable. If a man had said that you would come to this you would have struck him in the face.” But a life of begging for food and often receiving none caused many to turn to petty crime – pilfering eggs from the hen house, stealing apples from the orchard. Local officials considered tramps to be a public nuisance. Even the dictionary definition of tramp reflected this: “a foot traveler, often in a bad sense, a begging or thieving vagabond.”

Public opinion of tramps was split between those who believed they were down on their luck versus those who thought the men refused to work due to laziness. This old argument of the ‘worthy poor’ in contrast to the ‘unworthy poor’ had been floating around for centuries. Was it acceptable to provide aid or would that catapult them into a lifetime of dependency? The Progressives of the late 1890s believed that most tramps were honest men simply on hard times. Ossian Guthrie, observed in the Chicago Tribune of February 28, 1896: “After the war people looked forward to an era of crime, but the soldiers scattered over the country and settled down to the work they dropped when called to arms. With the return of prosperity in 1878, after a panic lasting five years, the tramp army melted. Where did they go? To work, as soon as there was work to be done. As the problem has solved itself in the past, so it will solve itself now. As business gradually improves, as factories start up and mines resume work with the old-time number of men, the tramp army will dwindle away till not more than 5 per cent, the really criminal portion is left.”

It was that criminal portion that concerned local officials. To keep the tramps from becoming a frightening threat, local police stations began lodging the men overnight. But while the practice had existed in earlier times – occasionally taking in one or two people and tossing them into the drunk tank with the locals, the numbers began rising in the 1890s. The News-Letter further commented, “Frequently 10 or more have been received on a single night and in one instance 18. The record for October was 136, for November 168, for December 170 and for January thus far 104. In the foregoing is included one woman. Measures which will abate the tramp nuisance are much to be desired.” In 1896, there were a total of 1007 ‘lodgers’ taken into the Exeter police station. The number continued to rise, topping out at 1366 in 1899. Then, as predicted by Ossian Guthrie, the job market began to open. The Police Commissioners were able to report in 1902, “the number of those unfortunates, called tramps, who have applied at the Police Station for lodgings has been considerably smaller than in past years.” 1902 saw only 340 requests for shelter – a number still quite high, but far lower than during the panic.

The number of tramps plateaued for several decades, not swelling again until 1934, when the Great Depression brought 1132 men into the police station. With no other means to manage the problem, the police continued to be the only source of shelter for homeless wanderers. After the new Safety Complex was built on Court Street in 1979, the practice was eliminated. By that time, there were more local organizations offering assistance. Today when people arrive at the police station in dire straits they are directed to Cross Roads House or the St. Vincent de Paul Society, both of which are better able to assist those in need.

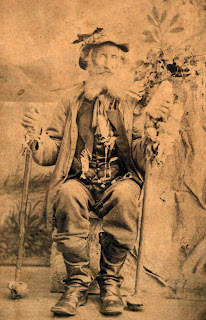

Photo: Most tramps were considered a nuisance, but this man, who called himself “King David” was a local character. Travelling through town in the 1880s, he would sell photos of himself, talk religion and stayed wherever the townsfolk would put him up – most likely the Exeter Police Station.

This "Historically Speaking" column was published by the Exeter News-Letter on Friday, November 6, 2015.

“Tuesday night was the first of the winter in which no tramps sought shelter at Exeter’s Police Station,” the Exeter News-Letter noted in January of 1897. Wandering vagrants had always been a problem in towns along the railroad line, but the number of such people increased in the 1890s. Some towns erected small ‘tramp houses’ to accommodate – and incarcerate – people overnight. A bed and perhaps a meal would be exchanged for a small odd-job, such as cutting firewood, and then the tramps would be escorted out of town in the morning.

There is a romantic view of life lived in the rough. Bart Kennedy wrote of his tramping days at the turn of the century in A Man Adrift. “It may be that you feel the sense of freedom that comes from a total lack of responsibility. No one is dependent upon you. No one is waiting for you. If people have contempt for you, at least they leave you alone. And this is something.” Most men – and tramps were generally single men – took to the wandering life after an economic downturn. The Panic of 1893, what we would today call a recession, threw men out of work in many industrial cities. Factory workers found themselves without jobs and with no social support system. In New England, textile workers were often the ones left without jobs. Mills, including the Exeter Manufacturing Company, thought nothing of shutting down for weeks or months to conserve funds, leaving employees with no means of support. “To be penniless and on tramp is a curious experience,” Kennedy observed, “It may have been that at one time in your life you would have thought it impossible for you to beg. You would have shuddered at the bare idea. How shameful! You would have thought death would be preferable. If a man had said that you would come to this you would have struck him in the face.” But a life of begging for food and often receiving none caused many to turn to petty crime – pilfering eggs from the hen house, stealing apples from the orchard. Local officials considered tramps to be a public nuisance. Even the dictionary definition of tramp reflected this: “a foot traveler, often in a bad sense, a begging or thieving vagabond.”

Public opinion of tramps was split between those who believed they were down on their luck versus those who thought the men refused to work due to laziness. This old argument of the ‘worthy poor’ in contrast to the ‘unworthy poor’ had been floating around for centuries. Was it acceptable to provide aid or would that catapult them into a lifetime of dependency? The Progressives of the late 1890s believed that most tramps were honest men simply on hard times. Ossian Guthrie, observed in the Chicago Tribune of February 28, 1896: “After the war people looked forward to an era of crime, but the soldiers scattered over the country and settled down to the work they dropped when called to arms. With the return of prosperity in 1878, after a panic lasting five years, the tramp army melted. Where did they go? To work, as soon as there was work to be done. As the problem has solved itself in the past, so it will solve itself now. As business gradually improves, as factories start up and mines resume work with the old-time number of men, the tramp army will dwindle away till not more than 5 per cent, the really criminal portion is left.”

It was that criminal portion that concerned local officials. To keep the tramps from becoming a frightening threat, local police stations began lodging the men overnight. But while the practice had existed in earlier times – occasionally taking in one or two people and tossing them into the drunk tank with the locals, the numbers began rising in the 1890s. The News-Letter further commented, “Frequently 10 or more have been received on a single night and in one instance 18. The record for October was 136, for November 168, for December 170 and for January thus far 104. In the foregoing is included one woman. Measures which will abate the tramp nuisance are much to be desired.” In 1896, there were a total of 1007 ‘lodgers’ taken into the Exeter police station. The number continued to rise, topping out at 1366 in 1899. Then, as predicted by Ossian Guthrie, the job market began to open. The Police Commissioners were able to report in 1902, “the number of those unfortunates, called tramps, who have applied at the Police Station for lodgings has been considerably smaller than in past years.” 1902 saw only 340 requests for shelter – a number still quite high, but far lower than during the panic.

The number of tramps plateaued for several decades, not swelling again until 1934, when the Great Depression brought 1132 men into the police station. With no other means to manage the problem, the police continued to be the only source of shelter for homeless wanderers. After the new Safety Complex was built on Court Street in 1979, the practice was eliminated. By that time, there were more local organizations offering assistance. Today when people arrive at the police station in dire straits they are directed to Cross Roads House or the St. Vincent de Paul Society, both of which are better able to assist those in need.

Photo: Most tramps were considered a nuisance, but this man, who called himself “King David” was a local character. Travelling through town in the 1880s, he would sell photos of himself, talk religion and stayed wherever the townsfolk would put him up – most likely the Exeter Police Station.

Comments