Lithuanians in Exeter

by Barbara Rimkunas

This "Historically Speaking" column was published in the Exeter News-Letter on Tuesday, July 21, 2014.

“Were there Lithuanians in Exeter?” I’m often asked this question, probably because my name and the Exeter Historical Society just don’t seem to match. Surely a New England town like ours should have a less ‘ethnic’ sounding curator. Fear not! All is well. Although I am, in fact, a transplant to this town, there were Lithuanians here before me who paved the way.

Tracking down Lithuanians seems like it should be easy, but there are a number of bumps along the way. The first problem is that Lithuania, as a country, didn’t actually exist for whole decades. Like Poland, the Baltic states of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania were often absorbed into other kingdoms and nations. The boundary lines were elastic enough that the people within could have a Polish name, but be ethnically Lithuanian or Russian – or any mixture of the three. So, it’s important to set some clear boundaries about Lithuanian immigration patterns to the United States.

There would not have been any immigration before 1861 unless one was a nobleman or wealthy merchant. Lithuania was under the governance of the Russian Empire, where the peasants were enserfed. Serfdom was not the same as slavery in a few critical ways – serfs were not technically ‘owned’ by a master, but they didn’t have freedom to travel or move from their land, so the landlord essentially controlled their lives. Women were expected to move to their husband’s family, but unless they were drafted into the Tsar’s army – a commitment of 25 years – men stayed put. So, no one was hopping a boat to America unless they lied about their origins. Abolition of serfdom occurred under Tsar Alexander II just a few years before Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation in this country.

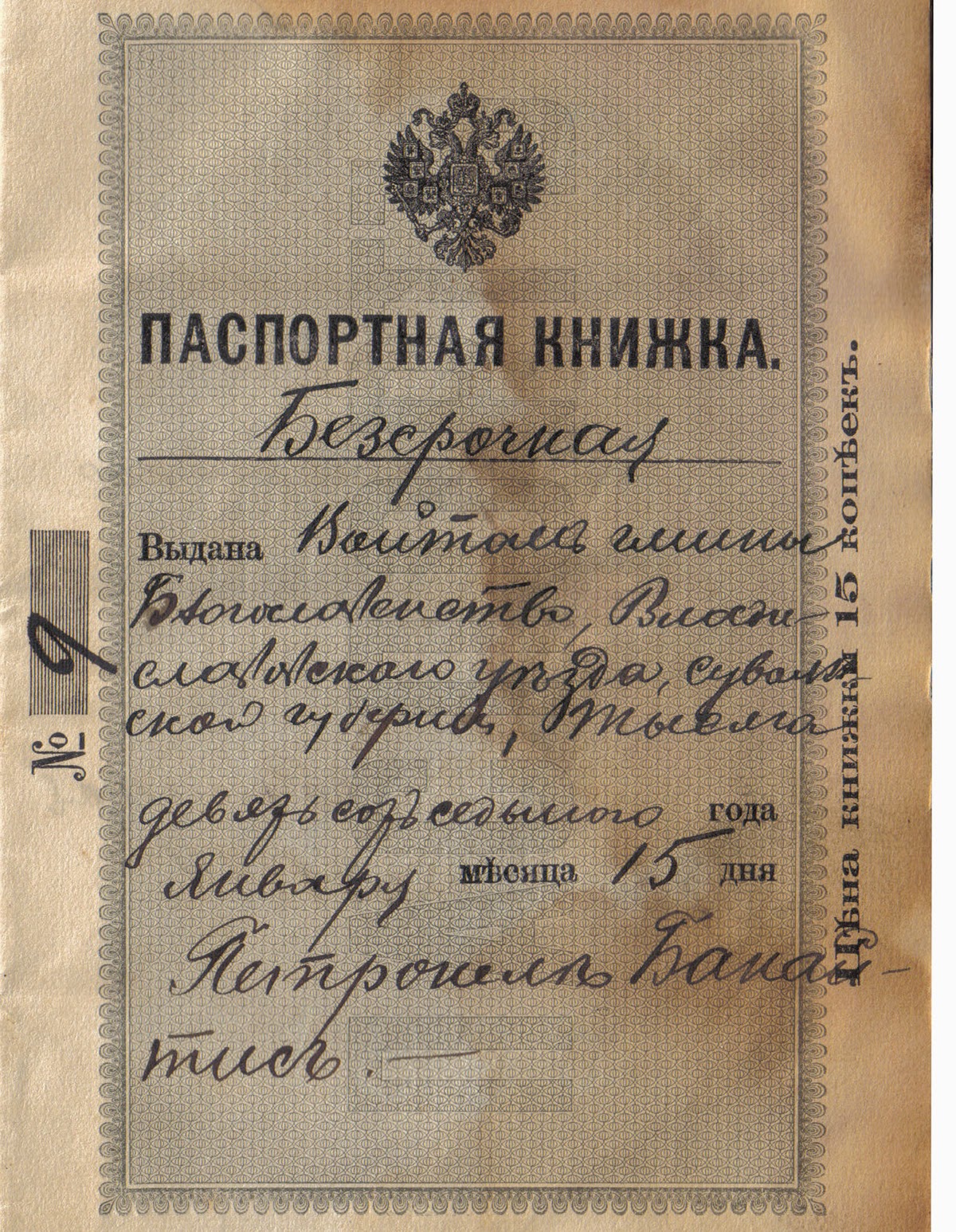

After emancipation, many Lithuanians began to consider emigration. Improved transportation, droughts, famines and repression of the ethnic minorities by the Russian Empire made the decision to leave quite attractive. People arriving from Lithuania were listed as ‘Russian,’ so any search must begin by looking for Russians. Indeed, a search of Exeter’s vital records does not mention Lithuania as a country of origin until 1913. My Great-Grandmother’s passport, issued in 1914, is entirely in Russian. To add insult to injury (at least for Petronella Benitis) her name on the second page includes a Russian patronymic, Simonovna – a derivation of her father’s first name, which she would never have used. Good thing she was illiterate. If she heard it read off at either her place of embarkation or Ellis Island, likely she swallowed her thoughts. For our part, the family is glad those hated Russians included the patronymic as it is our only clue about the identity of her father, Simon Benitis.

Lithuanians begin to arrive in Exeter in the 1880s. The first to arrive were Jewish immigrants who most likely were feeling Tsarist repression much deeper than the Catholic Lithuanians who followed them here twenty or so years later. Zelig London and his family were quickly joined by the Cohens and Golds by 1887. By 1902, there were more people turning up in Exeter’s vital records with ‘Russia’ as a country of origin. Once arrived, they found work in the many factories in town, married and began to have families. Most have names that are traditionally Lithuanian – ending in ‘as,’ ‘is’ or ‘us’ – such as, Mazaluskas, Paszukonis, Raziskis and Cilcius. I’m often told my name looks Greek for this reason. Many other names have a decidedly Polish feel, Debrowska, Kudroski, Vitkoska. These names appear in marriage records and birth registrations. But when we try to find out where the Lithuanian population lived in Exeter our town directories list no such people. By and large, the Lithuanians altered or completely changed their names – sometimes several times. We recently tried to find the Kopesci family for some visitors to the historical society using directories, census listings and vital records, and it took hours just to determine that they arrived in town with the name ‘Skopackas’ but also used ‘Skapescki’ before settling on Kopesci. Rather unusually, the name was altered to blend in better with the larger Polish population in Exeter, and not the overwhelming English blue-bloods who ran the town. I guess they needed to keep some bit of pride.

And by the way, names were NOT changed at Ellis Island. For some reason, lots of families have stories that their names were changed there, but it simply didn’t happen. I’ll direct you to an excellent article online: “Why Your Family Name Was Not Changed at Ellis Island” written by the staff of the New York Public Library. Names were often changed, but usually it was the immigrants who changed them. They quickly tired of Americans stumbling over what to them was a simple name. Seriously. “Rimkunas” is perfectly phonetic, yet I’ve heard all variations of it – usually with a “Q” inserted somewhere in the middle.

The first two decades of the 20th century brought a huge influx of immigrants to the United States. The numbers finally began to abate after 1924 when strict immigration quotas were enacted. Lithuanians in Exeter, as elsewhere in New England, stuck together – even forming a Lithuanian Club that served as a mutual assistance society paying death, sickness and disability benefits to members. Finding your Lithuanian ancestors can be challenging, but isn’t necessarily impossible. Just don’t call them Russians. They don’t like that.

Image: Lithuanians immigrating to the United States carried Russian passports, like this – the passport of Petronella Benitis, great-grandmother of the author.

This "Historically Speaking" column was published in the Exeter News-Letter on Tuesday, July 21, 2014.

“Were there Lithuanians in Exeter?” I’m often asked this question, probably because my name and the Exeter Historical Society just don’t seem to match. Surely a New England town like ours should have a less ‘ethnic’ sounding curator. Fear not! All is well. Although I am, in fact, a transplant to this town, there were Lithuanians here before me who paved the way.

Tracking down Lithuanians seems like it should be easy, but there are a number of bumps along the way. The first problem is that Lithuania, as a country, didn’t actually exist for whole decades. Like Poland, the Baltic states of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania were often absorbed into other kingdoms and nations. The boundary lines were elastic enough that the people within could have a Polish name, but be ethnically Lithuanian or Russian – or any mixture of the three. So, it’s important to set some clear boundaries about Lithuanian immigration patterns to the United States.

There would not have been any immigration before 1861 unless one was a nobleman or wealthy merchant. Lithuania was under the governance of the Russian Empire, where the peasants were enserfed. Serfdom was not the same as slavery in a few critical ways – serfs were not technically ‘owned’ by a master, but they didn’t have freedom to travel or move from their land, so the landlord essentially controlled their lives. Women were expected to move to their husband’s family, but unless they were drafted into the Tsar’s army – a commitment of 25 years – men stayed put. So, no one was hopping a boat to America unless they lied about their origins. Abolition of serfdom occurred under Tsar Alexander II just a few years before Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation in this country.

After emancipation, many Lithuanians began to consider emigration. Improved transportation, droughts, famines and repression of the ethnic minorities by the Russian Empire made the decision to leave quite attractive. People arriving from Lithuania were listed as ‘Russian,’ so any search must begin by looking for Russians. Indeed, a search of Exeter’s vital records does not mention Lithuania as a country of origin until 1913. My Great-Grandmother’s passport, issued in 1914, is entirely in Russian. To add insult to injury (at least for Petronella Benitis) her name on the second page includes a Russian patronymic, Simonovna – a derivation of her father’s first name, which she would never have used. Good thing she was illiterate. If she heard it read off at either her place of embarkation or Ellis Island, likely she swallowed her thoughts. For our part, the family is glad those hated Russians included the patronymic as it is our only clue about the identity of her father, Simon Benitis.

Lithuanians begin to arrive in Exeter in the 1880s. The first to arrive were Jewish immigrants who most likely were feeling Tsarist repression much deeper than the Catholic Lithuanians who followed them here twenty or so years later. Zelig London and his family were quickly joined by the Cohens and Golds by 1887. By 1902, there were more people turning up in Exeter’s vital records with ‘Russia’ as a country of origin. Once arrived, they found work in the many factories in town, married and began to have families. Most have names that are traditionally Lithuanian – ending in ‘as,’ ‘is’ or ‘us’ – such as, Mazaluskas, Paszukonis, Raziskis and Cilcius. I’m often told my name looks Greek for this reason. Many other names have a decidedly Polish feel, Debrowska, Kudroski, Vitkoska. These names appear in marriage records and birth registrations. But when we try to find out where the Lithuanian population lived in Exeter our town directories list no such people. By and large, the Lithuanians altered or completely changed their names – sometimes several times. We recently tried to find the Kopesci family for some visitors to the historical society using directories, census listings and vital records, and it took hours just to determine that they arrived in town with the name ‘Skopackas’ but also used ‘Skapescki’ before settling on Kopesci. Rather unusually, the name was altered to blend in better with the larger Polish population in Exeter, and not the overwhelming English blue-bloods who ran the town. I guess they needed to keep some bit of pride.

And by the way, names were NOT changed at Ellis Island. For some reason, lots of families have stories that their names were changed there, but it simply didn’t happen. I’ll direct you to an excellent article online: “Why Your Family Name Was Not Changed at Ellis Island” written by the staff of the New York Public Library. Names were often changed, but usually it was the immigrants who changed them. They quickly tired of Americans stumbling over what to them was a simple name. Seriously. “Rimkunas” is perfectly phonetic, yet I’ve heard all variations of it – usually with a “Q” inserted somewhere in the middle.

The first two decades of the 20th century brought a huge influx of immigrants to the United States. The numbers finally began to abate after 1924 when strict immigration quotas were enacted. Lithuanians in Exeter, as elsewhere in New England, stuck together – even forming a Lithuanian Club that served as a mutual assistance society paying death, sickness and disability benefits to members. Finding your Lithuanian ancestors can be challenging, but isn’t necessarily impossible. Just don’t call them Russians. They don’t like that.

Image: Lithuanians immigrating to the United States carried Russian passports, like this – the passport of Petronella Benitis, great-grandmother of the author.

Comments