Scottish Prisoners in Exeter

by Barbara Rimkunas

This "Historically Speaking" column was published in the Exeter News-Letter on Friday, July 13, 2007.

“Hello, I’m looking for the burial site of Alexander Gordon.” This frequent phone query sometimes makes me want to record the following message on our answering machine: “You have reached the Exeter Historical Society, we are open for genealogical research but we do not know where Alexander Gordon is buried.”

Alexander Gordon was the first Gordon to come to America and I realize that it is important for his genealogically curious descendants to want to find his final resting place. It’s just that we really don’t know exactly where he is buried. The best we can do is direct them to the Perkins Hill Cemetery, formerly the Gordon Hill Cemetery, and reassure them that Alexander Gordon’s son, Thomas, left his entire estate including, “half an acre of land to be reserved for a Burying place” to his own sons. As he had inherited the land from his father, it is more than likely that somewhere on the hill is the final resting place of Alexander Gordon. If it is, then Perkins Hill is the setting for the final chapter of a very exciting biography.

There was very little immigration from Scotland to New England in the early 1600s. The Scots were usually Presbyterians who tended to clash with New England Puritans. They also didn’t speak English, they spoke a form of Highland Gaelic, which may surprise many people today. During the volatile period of the English Civil War, Oliver Cromwell’s forces attacked Scotland not once but twice, both resulting in crushing Scottish defeats. At both the battles of Dunbar, in 1650, and Worcester, in 1651, thousands of very young Scotsmen were marched to England as prisoners of war. Most of them were in their teens and early twenties and it would have been dangerous to allow them to return to Scotland after the war ended. Angry young men tend to hold a grudge. The decision was made to sell the able-bodied into servitude in the colonies.

Fifteen year old Alexander Gordon was caught up in the conflict. Marched miserably to London to await transportation, he survived the cold and near starvation long enough to win a miserable three to four month cruise on an overcrowded fetid ship bound for the wilderness of America. Upon arrival in Massachusetts, he was sold for between 15 – 30 pounds for six years unpaid service. Americans were quite used to the system of indentured servitude, but the Scotsmen were not. They tried, unsuccessfully, to use the colonial legal system to shorten their terms of service. Gordon himself filed suit in 1654 against John Cloyce, claiming he had been defrauded. Most of these cases were dismissed. After his attempt to manipulate the legal system, Gordon disappears from the record only to reappear in 1664 in Exeter, New Hampshire. There we find him working at the saw mill of Nicholas Lissen on the Exeter River.

Lissen, an Englishman by birth, seems to have preferred the company of Scottish prisoners of war. He hired, or perhaps bought indentures of, at least three of them: Gordon, John McBean, and Henry Magoon. Conveniently, Lissen had three daughters and one after another they married the Scotsmen. Hannah married John Bean (he dropped the “Mc”) in 1654, Elizabeth and Henry Magoon were wed in 1657, and Mary hooked up with Alexander Gordon in 1663. One way to escape servitude, apparently, was to marry the owner’s daughter. All three men became landowners and partners in the saw mill. Another former prisoner in Exeter was John Sinkler, who worked in a saw mill on the other side of town.

The Scotsmen who came to Exeter all stayed and became equal citizens. According to Diane Rapaport, a writer on the subject, “There is little evidence that any of the men went back to Scotland” after they’d served their time. “What happened to the Scotsmen at that point varied greatly, depending upon who had owned them and where, whether they could read or write, and how well they could speak English.” The Lissen sisters must have been good teachers, because not only are there still a lot of Beans and Magoons living in New England, the Gordon Family returns to Exeter with some regularity to visit the spot where Alexander might be buried.

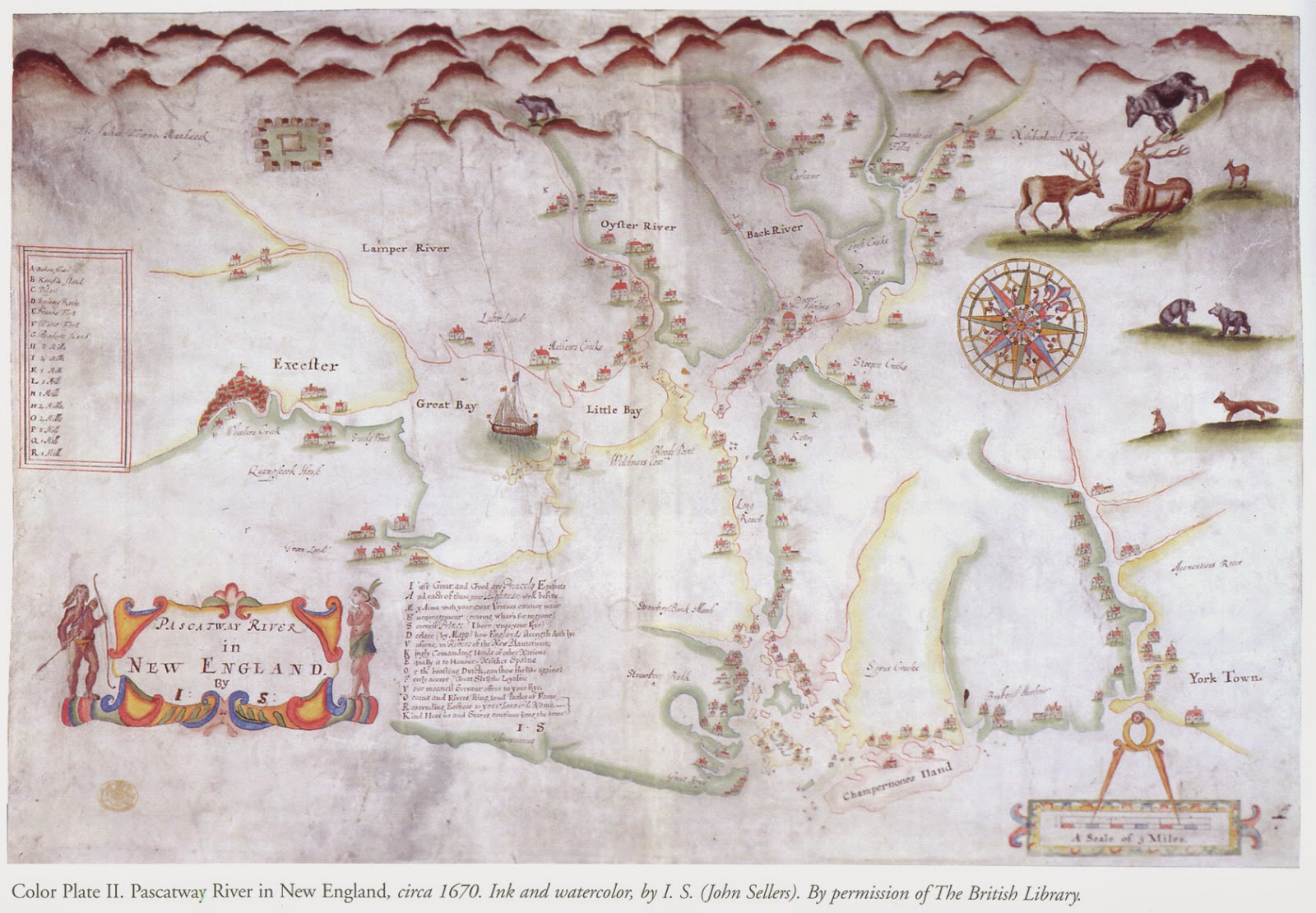

Image: The densely forested Piscataqua region of New Hampshire and Maine (depicted here in the 1670s) created a need for labor at the saw mills. Local mill owners were more than willing to purchase Scottish prisoners, who would then work off an indenture of 6-8 years with no compensation. Descendants of these prisoners still live in the region.

This "Historically Speaking" column was published in the Exeter News-Letter on Friday, July 13, 2007.

“Hello, I’m looking for the burial site of Alexander Gordon.” This frequent phone query sometimes makes me want to record the following message on our answering machine: “You have reached the Exeter Historical Society, we are open for genealogical research but we do not know where Alexander Gordon is buried.”

Alexander Gordon was the first Gordon to come to America and I realize that it is important for his genealogically curious descendants to want to find his final resting place. It’s just that we really don’t know exactly where he is buried. The best we can do is direct them to the Perkins Hill Cemetery, formerly the Gordon Hill Cemetery, and reassure them that Alexander Gordon’s son, Thomas, left his entire estate including, “half an acre of land to be reserved for a Burying place” to his own sons. As he had inherited the land from his father, it is more than likely that somewhere on the hill is the final resting place of Alexander Gordon. If it is, then Perkins Hill is the setting for the final chapter of a very exciting biography.

There was very little immigration from Scotland to New England in the early 1600s. The Scots were usually Presbyterians who tended to clash with New England Puritans. They also didn’t speak English, they spoke a form of Highland Gaelic, which may surprise many people today. During the volatile period of the English Civil War, Oliver Cromwell’s forces attacked Scotland not once but twice, both resulting in crushing Scottish defeats. At both the battles of Dunbar, in 1650, and Worcester, in 1651, thousands of very young Scotsmen were marched to England as prisoners of war. Most of them were in their teens and early twenties and it would have been dangerous to allow them to return to Scotland after the war ended. Angry young men tend to hold a grudge. The decision was made to sell the able-bodied into servitude in the colonies.

Fifteen year old Alexander Gordon was caught up in the conflict. Marched miserably to London to await transportation, he survived the cold and near starvation long enough to win a miserable three to four month cruise on an overcrowded fetid ship bound for the wilderness of America. Upon arrival in Massachusetts, he was sold for between 15 – 30 pounds for six years unpaid service. Americans were quite used to the system of indentured servitude, but the Scotsmen were not. They tried, unsuccessfully, to use the colonial legal system to shorten their terms of service. Gordon himself filed suit in 1654 against John Cloyce, claiming he had been defrauded. Most of these cases were dismissed. After his attempt to manipulate the legal system, Gordon disappears from the record only to reappear in 1664 in Exeter, New Hampshire. There we find him working at the saw mill of Nicholas Lissen on the Exeter River.

Lissen, an Englishman by birth, seems to have preferred the company of Scottish prisoners of war. He hired, or perhaps bought indentures of, at least three of them: Gordon, John McBean, and Henry Magoon. Conveniently, Lissen had three daughters and one after another they married the Scotsmen. Hannah married John Bean (he dropped the “Mc”) in 1654, Elizabeth and Henry Magoon were wed in 1657, and Mary hooked up with Alexander Gordon in 1663. One way to escape servitude, apparently, was to marry the owner’s daughter. All three men became landowners and partners in the saw mill. Another former prisoner in Exeter was John Sinkler, who worked in a saw mill on the other side of town.

The Scotsmen who came to Exeter all stayed and became equal citizens. According to Diane Rapaport, a writer on the subject, “There is little evidence that any of the men went back to Scotland” after they’d served their time. “What happened to the Scotsmen at that point varied greatly, depending upon who had owned them and where, whether they could read or write, and how well they could speak English.” The Lissen sisters must have been good teachers, because not only are there still a lot of Beans and Magoons living in New England, the Gordon Family returns to Exeter with some regularity to visit the spot where Alexander might be buried.

Comments